Tracing the history of enclosure with Eula Biss, collecting modern stories of commoning with Future Natures, dreaming and planning for a Half Earth Socialist future, and a little bit of solarpunk.

The Theft of the Commons

I immediately devour anything written by Eula Biss, so was very excited to see this article by her in the Sentiers newsletter a few weeks ago.

In the essay, she traces the history of the commons and enclosure, which began here in the UK.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

She debunks that awful essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” by the white nationalist Garrett Hardin. It’s so unfortunately that this idea / phrase has somehow wormed itself into popular consciousness when talking about the commons. It’s been decisively disproven by Elinor Ostrom, who became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for her work.

One of the things I love about Biss’ work is her ability to weave together so many different strands, wandering across topics like capitalism, feudalism, luddites, gleaners, nostalgia, art, myths, symbols, language, class.

I loved this quote:

The history of the distant past is often speculative. Like science fiction, it gives us a way of thinking about what might be possible, as much as what might have been. In this sense, both the past and the future are imaginary, but real, too, as ideas.

It ties in with the ideas from The Dawn of Everything, which we’re currently reading in Re-re-re-reading Group. In it, the Davids retell history to open up our imaginations, challenge commonly held beliefs and suggest that we might have done life and politics and society very differently in the past (and therefore, we might be able to do it differently again.)

“Would you go back?” strikes me as the wrong question to ask of nostalgia. The question, as Zadie Smith puts it, is how to “restate the things you find valuable in the past… in a way that’s livable in this contemporary moment.” How to locate the commons in a world that is mostly enclosed. How to recover a tradition of rebellion against monied claims to property. How to use machines rather than be used by them. How to be canny, like the workers of the past, and how to be conservationists, like commoners. We can learn from the time before enclosure, but we can’t go back there.

Eula Biss’ other books include Having and Being Had, about money, ownership, capitalism and class and On Immunity, about pandemics, vaccinations, individualism and community. Cannot recommend them enough.

Future Natures

Speaking of the commons, we just launched a new website for Future Natures, which explores the “emergent ecologies of commoning and enclosure through stories, arts and research.” It was such a great project to work on – the team was so easy to collaborate with and their research is so interesting. They have big plans for building up an international network of commoners so I’m really excited to see where it goes.

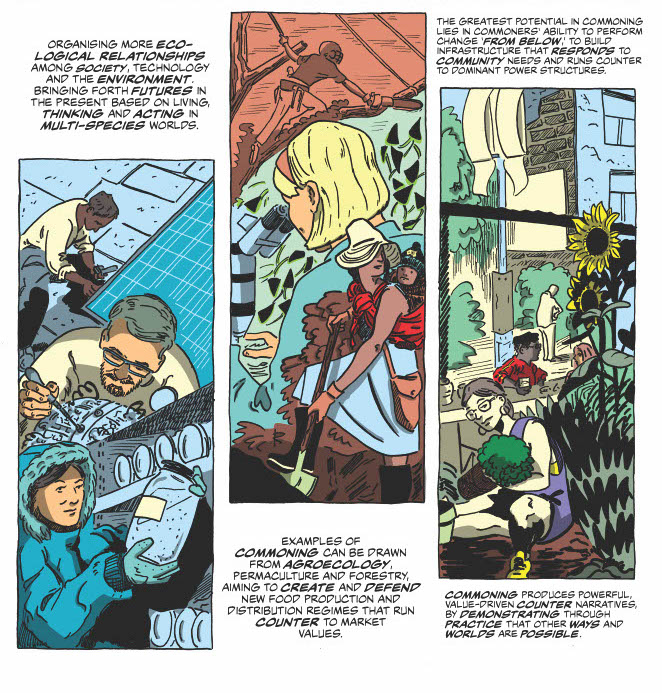

They’ve created this incredible comic that also explores the history of enclosure, the intersecting crises we’re living through and what commoning is and can be.

Half Earth Socialism

I’ve just finished reading Half Earth Socialism by Drew Pendergrass and Troy Vettese.

I was really impressed. It’s a short but dense book that covers a lot of ground, like a non-fiction chaser to The Ministry for the Future. They criticise mainstream environmental solutions, paint a picture of what a socialist utopia might look like (including a speculative fiction chapter inspired by William Morris’ News From Nowhere, which is clunky but quite sweet) and outline a clear plan on how to get there.

Enough should be a human right, a floor below which no one can fall; also a ceiling above which no one can rise. Enough is as good as a feast—or better.

— Kim Stanley Robinson, Ministry for the Future

They also worked with Francis Tseng and Son La Pham to create a Half Earth Socialism game. I played it straight after finishing the book. It was really fun and helped drill home some of their ideas. It felt very moving to be able to pass policies and take action to address climate change, and then to watch as these played out and some of our worst possible futures be avoided.

On the other hand, it felt overwhelming to think on a global scale and 80 years into the future. While I agree with most of the ideas that the book proposes, just the thought of us actually succeeding to implement them at the speed and scale we need feels almost impossible. Still, I think it’s so useful to have these ideas laid out so clearly, as a discussions point or north star.

Your lifetime bridges centuries of harm that set the stage for climate change and centuries of healing that need to start now. Just be a bridge.

– Elizabeth Sawin

Refuge for Resurgence

We went to the Barbican’s Our Time on Earth exhibition a few weeks ago. It was pretty disappointing. It’s probably partially because I spend a lot of time thinking and reading about these topics already, but the ideas they proposed just seems so cliched/unambitious/self-indulgent. Eirini Malliaraki summarises it well in this thread.

However, I did enjoy the window view designed by Superflux and Sebastian Tiew – love a bit of post-capitalist solarpunk ambiguous utopia!