I’ve just come back from an inspiring week at the Community Economies in Action practice retreat in Terragnolo, Italy. It was designed and facilitated by Bianca Elzembaumer, Kate Rich and Flora Mammana as a practical counterpart to the Community Economies Institute’s summer/winter school.

There were 24 participants with a diverse range of practices: academics and researchers, artists and designers, gardeners and organisers. Everyone was somehow involved in community economies, whether through a food / worker / housing cooperative, ecovillage, market garden, urban landscape, band, radio program, library of things or design lab. Over the week, we learned about all these diverse forms of commoning, exchanged ideas and identified new methods for collaborative survival. We were encouraged to be honest with each other about our struggles as well as celebrating our successes.

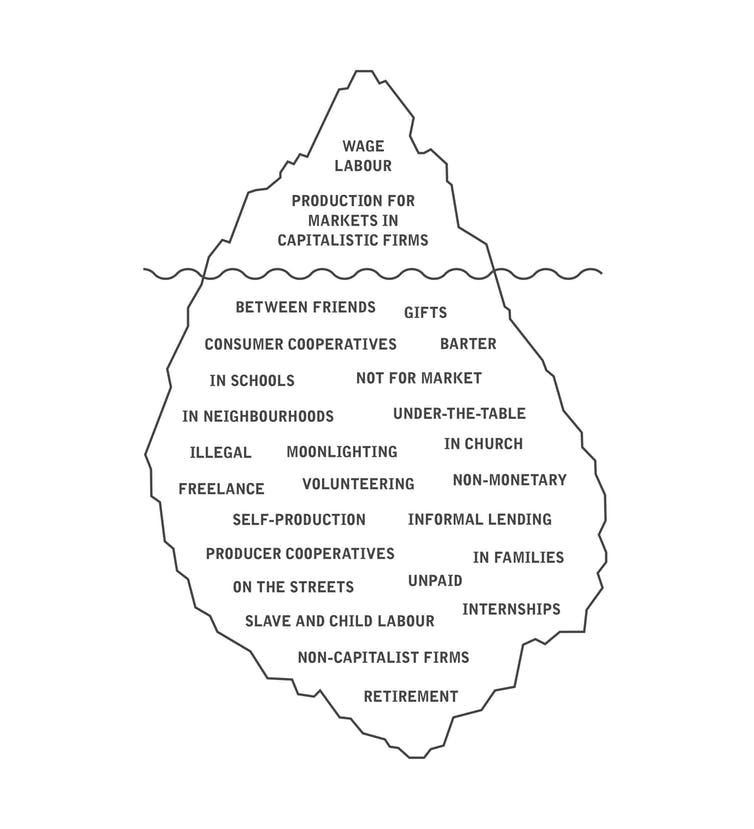

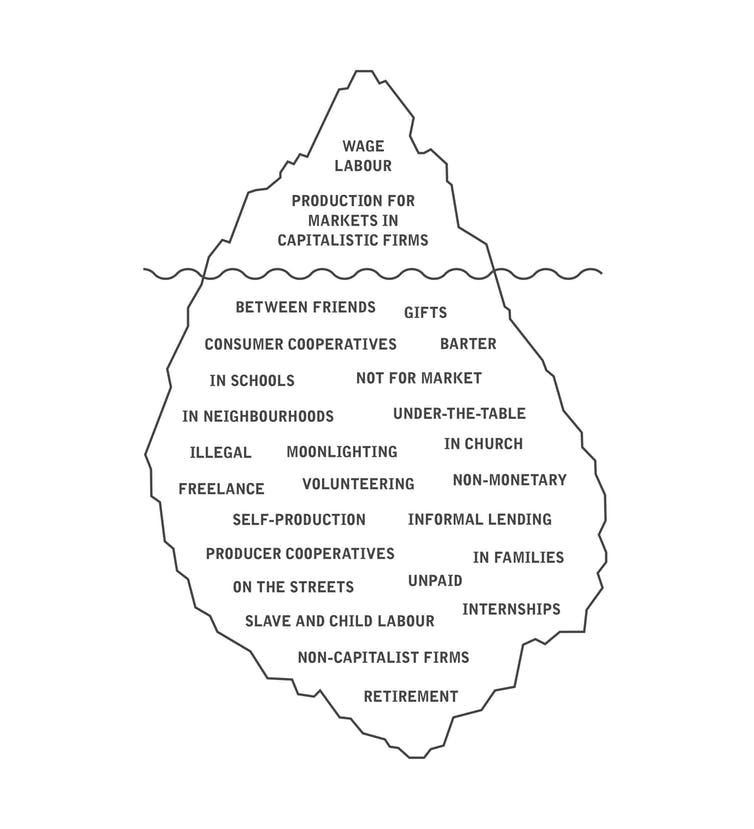

Underpinning the retreat were the ideas of J.K. Gibson-Graham, two feminist geographers from Sydney who collectively wrote books like The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It) and Take Back The Economy. Their work is all about rethinking the economy by foregrounding diverse economic practices and giving them credibility. These diverse economies include unpaid labour, cooperatives, Community Supported Agriculture, alternative currencies, voluntary organisations, underground economies, gift giving, foraging and barter.

▲ Iceberg model diagram by Bianca Elzembaumer, Brave New Alps

The programme itself was quite emergent, with open spaces where we could propose our own ideas and free time for rest and reflection. Although there were some readings and a lot of deep thinking, there was also a strong focus on connecting with the land and with our bodies. We learned about the long history of commoning in the valley from our host Gianni of Il Masetto. One afternoon we went for a hike on a nearby mountain and foraged edible plants. We did a contact improvisation dance, swam in the river many times and cooked food together.

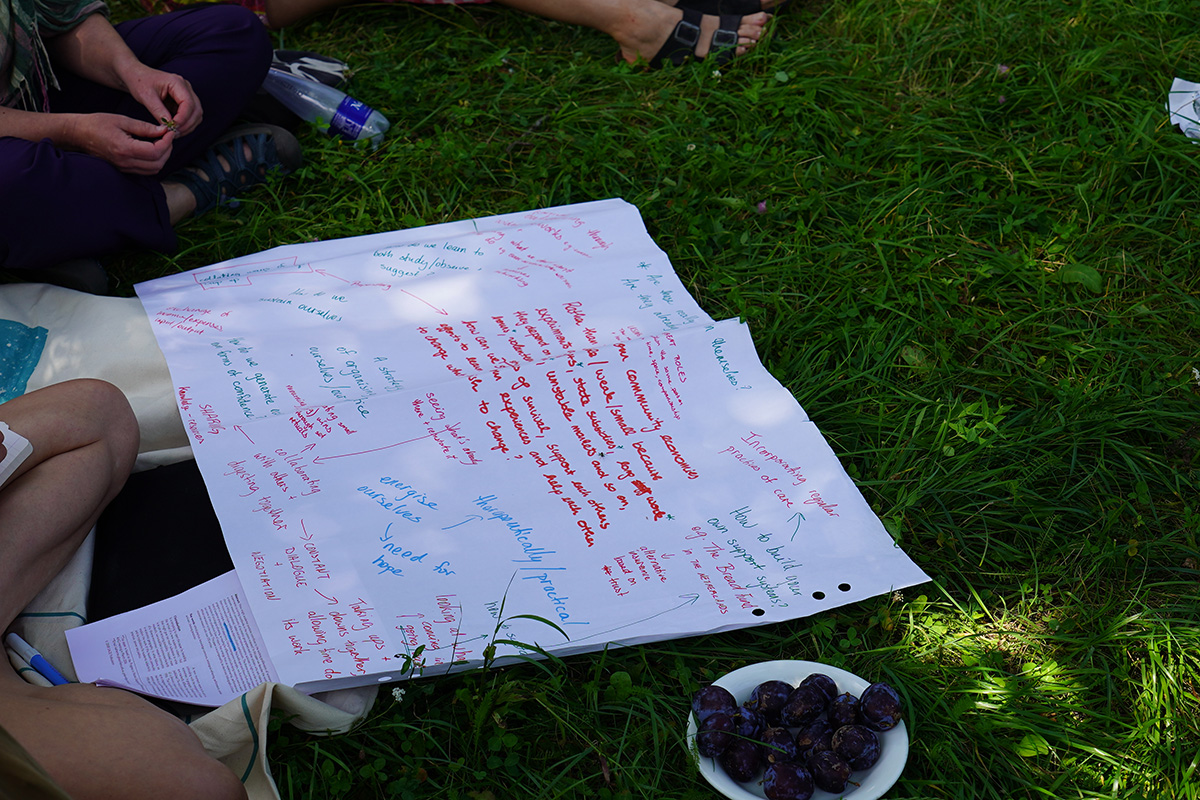

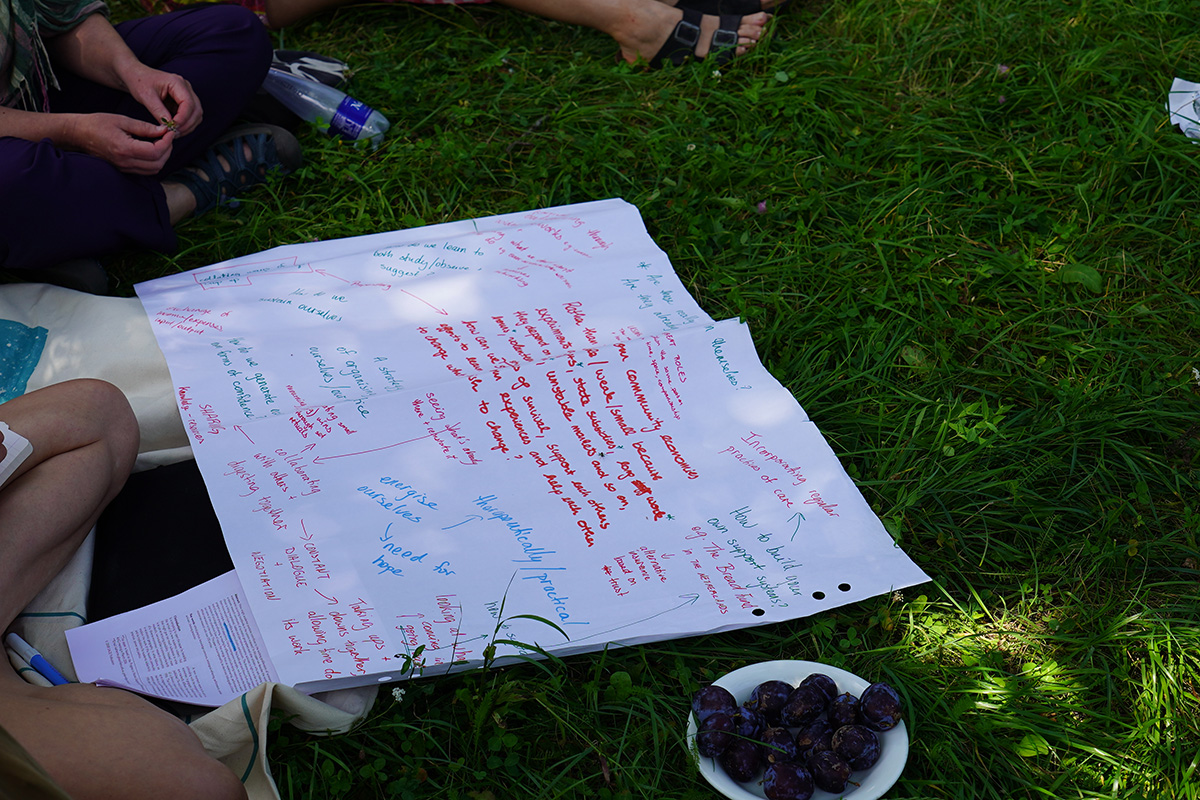

▲ Photos by Flora Mammana

Economy as Ecological Livelihood

We read two of their essays and reflected on the conversations they opened with our practices. The first, Economy as Ecological Livelihood by J.K. Gibson-Graham and Ethan Miller, suggested that we need to see the economy as something deeply entangled with everything else (social and ecological) rather than some separate sphere of human activity.

If we cease to think of ourselves as singular, self-contained beings and begin to think alongside, for example, the multiple communities of bacteria and bacterial symbionts from which we continually take shape and of which we are but fleeting, temporary manifestations (Hird 2009; Hird 2010); or if we place our activities in the context of the billions-of-years-old, emergent, planetary-scale process of bio- logical self-construction known as “Gaia” (Lovelock 2000; Harding 2006; Volk 2003), it is no longer possible to identify a singular “humanity” as a distinctive ontological category set apart from all else.

What difference might it make if we accept that from the scale of Gaia, to the scale of the microscopic bacteria that form the laboring basis for nearly all biological energy production and transformation, there is a “we” bound together in myriad interrelationships that are themselves the very conditions of existence for our sense of a human “we”? Being-in-common—that is, community—can no longer be thought of or felt as a community of humans alone; it must become multispecies community that includes all of those with whom our livelihoods are interdependent and interrelated.

They suggest four ethical coordinates to navigate the question “How do we live together with human and non-human others?”:

PARTICIPATION: Who is the “we” that participates in the constitution of livelihoods and community economies? This involves cultivating forms of knowing and becoming that open us to the complexities of our interdependencies, to their animate interactions with us, and to the forms of responsibility this calls forth.

NECESSITY OR SUFFICIENCY: What do “we” need for survival? What constitutes “enough”? This includes asking about what is necessary for the dignified survival of all living beings and communities with whom we are inter-dependent, and about how we might consume in ways such that one species’ or community’s consumption does not compromise the survival chances of others.

SURPLUS: How do “we” produce, appropriate, distribute and mobilize surplus? Our new accounting must include surplus that is generated not just by human labor, but by the work of plants, animals, bacteria, fungi and dynamic energetic systems.

COMMONS: How do “we” make and share a commons, the material commonwealth of our community economies, with this new, more-than-human “we” in mind? Can we, for example, begin to see the chickens, bees and fruit trees of a cooperative farm not as part of that farm’s commons (as shared resources), but rather as living beings partici- pating in the co-constitution of the community that, together, makes and shares the farm?

Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for ‘Other Worlds’

The second text, Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for Other Worlds, highlights all the diverse economic practices that already happening in the here and now.

Gibson-Graham take a post-structuralist approach to the idea of capitalism. Rather than just adding new or forgotten categories to the existing definition, they instead want to completely restructure how we understand the economy. Economic activities are usually defined in terms of their relationship to capitalism, the master signifier — everything exists in relation to it, whether that’s as a complement or supplement, against or within.

In The end of capitalism we addressed familiar representations of capitalism as an obdurate structure or system, coextensive with the social space. We argued that the performative effect of these representations was to dampen and discourage non-capitalist initiatives, since power was assumed to be concentrated in capitalism and to be largely absent from other forms of economy. In the vicinity of such representations, those who might be interested in non-capitalist economic projects pulled back from ambitions of widespread success – their dreams seemed unrealizable, at least in our lifetimes. Thus capitalism was strengthened, its dominance performed, as an effect of its representations.

They argue that we need to move instead to seeing capitalist practices as one element within a landscape of diverse economies. By moving beyond this capitalocentric viewpoint, we open up space for imagination and new possibilities. We can begin to imagine new worlds that we want to participate in building.

What if we were to accept that the goal of theory is not to extend knowledge by confirming what we already know, that the world is a place of domination and oppression? What if we asked theory instead to help us see openings, to provide a space of freedom and possibility?

▲ Photos by Flora Mammana

We discussed the text together, asking ourselves:

- How are we making ourselves open to the possibility of new economic becomings?

- How do our practices already contribute to the exciting proliferation of economic experiments occurring worldwide in the current moment?

- How can we study our strategies of survival, support each other’s efforts and help each other change what we wish to change?

I found the discussion and the overall framing incredibly generative. Rather than seeing ourselves as fighting against some all-encompassing, all-powerful system, it’s about shifting focus to seeing all the diverse possibilities that already exist and that could exist in the near future. Our discussion was focused in on the tangible and the concrete: what we’re already doing, what resources we already have, useful tools and techniques to continue and deepen this work. There is something so optimistic and playful about this approach.

Our interest in building new worlds involves making credible those diverse practices that satisfy needs, regulate consumption, generate surplus, and maintain and expand the commons, so that community economies in which interdependence between people and environments is ethically negotiated can be recognized now and constructed in the future.

We spoke to Katherine Gibson via Zoom one morning. One question that someone asked her was around critique and resistance — how do you keep proliferating possibilities when the whole system is working against you? She suggested that we don’t need to make things harder for ourselves by imagining big bad capitalism always waiting around the corner to gobble up our attempts. It’s easy to be angry at what’s there, it’s much harder to imagine and create desire for the not-quite-yet. You have to imagine that it is possible to create new worlds, working with fragments and wreckages, balancing fighting with building.

Feral Clinics

We did two mornings of Feral Clinics, a practice adapted from Kate Rich’s Feral MBA and previous iterations of this retreat. Each collective or practitioner took turns hosting a session, arriving with one crucial question that they’re currently facing in their practice. The rest of the group took turns either asking questions or holding space, helping the host to work through their own problems through active listening and thoughtful questions. Rather than asking questions out of your own curiosity, we were encouraged to ask questions based on what the person needed to hear, to help them draw their own conclusions.

In the first round, we helped the host fine-tune their question to the group. In the second round, we helped them proliferate possibilities. In the final round, we helped them identify the next, most elegant steps — a term that adrienne maree brown uses to refer to small, achievable and exciting steps forward, so easy to make that they feel like dancing.

Thinking about…

Focus on critical connections more than critical mass—build the resilience by building the relationships.

— adrienne maree brown

The week opened up a lot of questions for me. I found it challenging at times because I started to doubt my own practice, particularly in relation to digital technology. At Common Knowledge, we focus on understanding patterns shared by a broad range of political organisations and using the affordances of technology to help scale up their activities. It felt a long way from the practices of other people there, which was much more place-based, focused on working with their own local community.

I was lucky to have a two-hour mentoring session with Ethan Miller remotely from his housing co-op in Wabanaki Territory / Maine. I feel so grateful for the facilitators for setting this up because there were so many overlaps between the questions I had for my own practice and the work that he’s been doing for decades. We spoke about the challenges of being part of cooperatives and other non-hierarchical organisation models, how they set up their Community Land Trust, feminist science fiction, building capacity and desire within communities, being rooted in a particular place, commoning infrastructure… lots for me to think about!

I found it really heartening that quite a few of the other people there were also puzzled about where to live and how to balance the desire/need to travel with the need to belong to one community. I find it really difficult, as an immigrant from Australia who has lived for the last 12 years in The Netherlands, the UK and now Portugal, to understand where I belong. I also can’t imagine a life where I stay in one place and never travel — I would lose connection with so many of my friends and family, to familiar landscapes and to my past. At the same time, I feel a real need to slow down and feel rooted in one place.

Some of the questions I want to explore further are:

-

How can we work on a local community level and respond to all the idiosyncrasies of a specific place, but also still make sure we’re connecting with other initiatives, learning from each other, sharing resources and acting in ways that will have an impact on the planetary challenges we face?

-

When does it make sense to stay small, and when does it make sense to start organising on the national or international level?

-

What does place-based, small scale, low tech, convivial technology actually look like?

-

Is there a way to have community if you also need to travel? Can we develop communities across borders, with protocols and rituals than ensure a fair exchange between rooted and transient types? Can we develop new models of kinship and solidarity that enfold all these different needs and contradictions?

-

How do we create the desire for self-governance and economic experimentation in more people?

PS — How & I chatted to Vida from Robida Collective about the retreat when we visited Topolò last week — listen here.