— Everything is deeply intertwingled

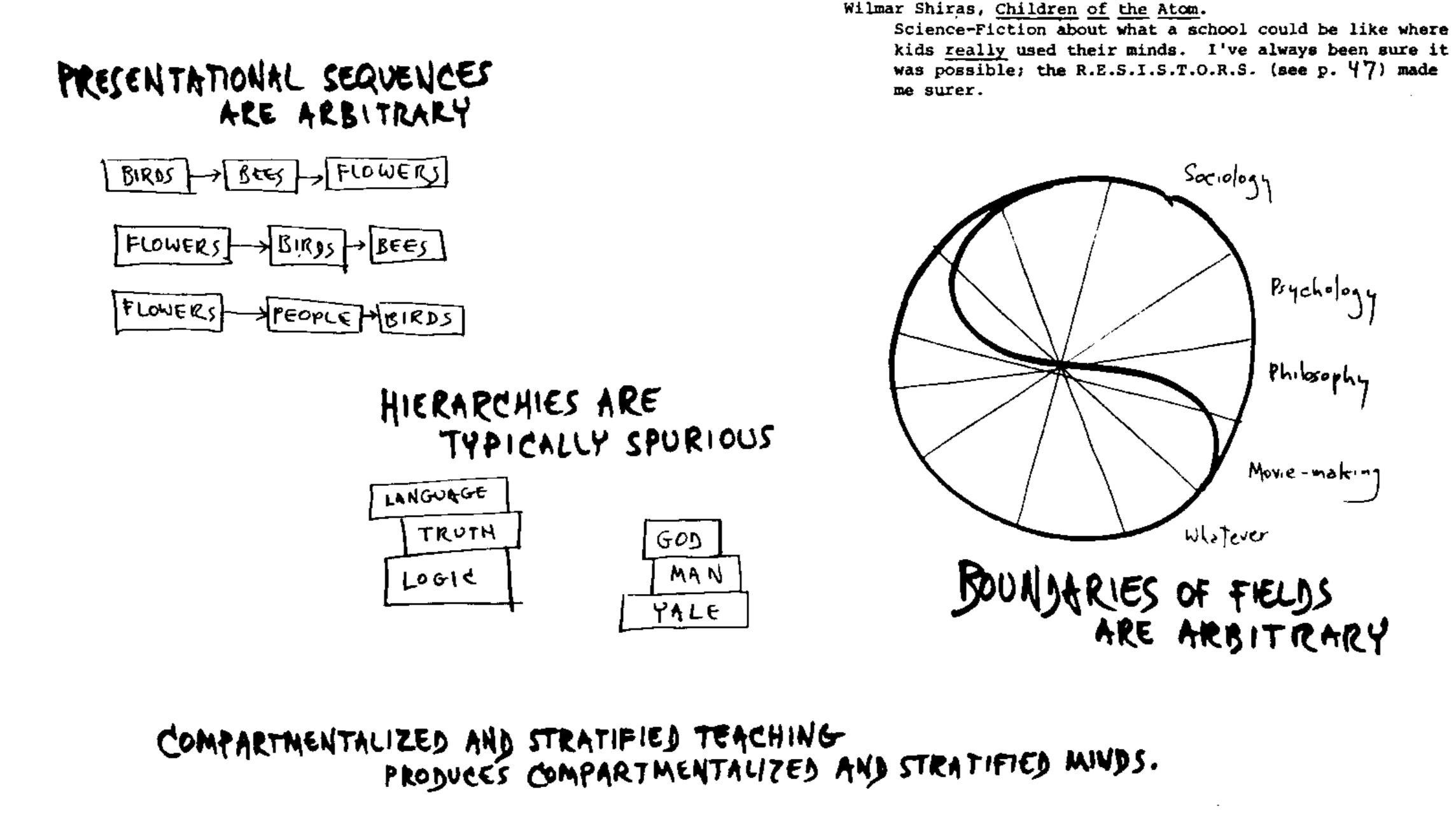

The structures of ideas are not sequential. They tie together every whichway. And when we write, we are always trying to tie things together in non-sequential ways. The footnote is a break from sequence, but it cannot really be extended. The point is, writers do better if they don’t have to write in sequence (but may create multiple structures, branches and alternatives), and readers do better if they don’t have to read in sequence, but may establish impressions, jump around, and try different pathways until they find the ones they want to study most closely.

▴ From Computer Lib / Dream Machines by Ted Nelson

I’ve recently started using Obsidian as a note-taking tool. It’s so interesting to observe how its affordances shape the way I think. The core app is beautifully minimal — a simple interface for editing local markdown files — which makes it super fast, secure and offline-first. You can extend this core functionality by installing plugins built by the community. I love this approach to software: letting people customise their own experience rather than trying to build the entire spectrum of features into the main product.

The main feature of Obsidian is that you can add backlinks as you write. I love being able to link all my thoughts together so fluidly. It makes the process of writing feel different: more like tending a garden. I think carefully about how I categorise ideas and spend more time revisiting past entries.

A few of the projects we’ve worked on at Common Knowledge lately have been digital gardens or wikis, where the usual hierarchical sitemaps don’t capture the interconnectedness of their structure. This prompted me to suggest that we read Christopher Alexander’s foundational text The City is Not a Tree in Rererereading Group recently. For fun, here’s Readwise’s GPT summary of the essay:

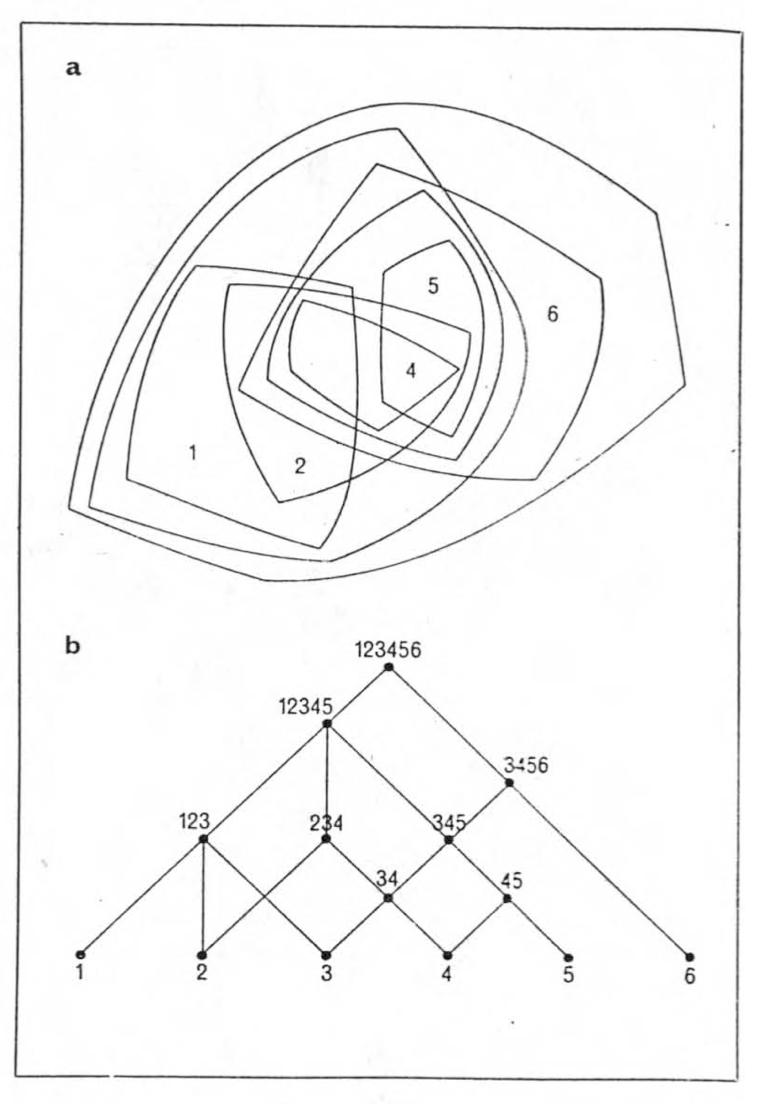

This text looks at the difference between structures (trees and semilattices) which are used to think about how a large and complex system is made up of many small systems. It is argued that the tree structure, which has been adopted by many designers and planners when creating artificial cities, is inadequate and cannot properly reflect the reality of the city’s social structure. It is proposed that the semilattice structure, which allows for overlap between elements, is a better representation of the living city, and should be adopted instead.

I think a digital garden full of bidirectional links is a kind of semilattice. The content can be collected, remixed and resurfaced in many different ways, appearing in lots of different sets according to the context. Working in this way requires a whole different approach to design. It’s complex and nonlinear, which can be challenging to get your head around compared to a tree website. Instead you have to understand it from the bottom-up, thinking in sets or patterns instead of trying to establish a top-down map or plan.

In simplicity of structure the tree is comparable to the compulsive desire for neatness and order that insists the candlesticks on a mantelpiece be perfectly straight and perfectly symmetrical about the centre. The semilattice, by comparison, is the structure of a complex fabric; it is the structure of living things, of great paintings and symphonies. It must be emphasized, lest the orderly mind shrink in horror from anything that is not clearly articulated and categorized in tree form, that the idea of overlap, ambiguity, multiplicity of aspect and the semilattice are not less orderly than the rigid tree, but more so. They represent a thicker, tougher, more subtle and more complex view of structure.

▴ From The City is Not a Tree by Christopher Alexander

In Towards Growing Peaches Online, Claire L. Evans writes about Christopher Alexander and what he referred to as “living structure”. She describes how A Pattern Language influenced software development in general and the design of Are.na more specifically.

Living structure is the natural order of life lived at human-scale. A compost heap has living structure. So does a good bus system, or a small public square. You can feel it in the difference between a lovely old building and a sterile new development; one is built by its inhabitants, and the other is designed by architects. “When a place is lifeless or unreal, there is almost always a mastermind behind it,” Alexander writes. “It is so filled with the will of the maker that there is no room for its own nature.” On the other hand, things with living structure feel right; they’re harmonious.

To me, there’s something so exciting about this approach. Instead of designer as author/architect, it’s designer as facilitator: creating the space for unexpected things to happen; for emergence, indeterminancy, ambiguity. (I’ve written a bit more about this here.)

What this means, really, is a rethinking of one’s own position as a creator. You stop thinking of yourself as me, the controller, you the audience, and you start thinking of all of us as the audience, all of us as people enjoying the garden together.

▴ From Composers as Gardeners by Brian Eno

One of the features I love about Are.na is that the sidebar of each block lists all the other channels that it has been connected to in the sidebar. This helps to prompt further exploration and strengthen connections to the rest of the community. Similarly, Obsidian notes have an Unlinked mentions section that surfaces any occurances of the current note’s title in other notes. It’s Ted Nelson’s dream of hypertext in action!

The task of hypertext is not to manufacture connections, but to discover where they have always been. Hypertext researchers before the World Wide Web built systems to support this endless, sacred hunt for entanglement and hidden structure, as inherent to thought as ecosystems are to the natural world.

▴ From Women in Hypertext: On Judy Malloy and Cathy Marshall’s Forward Anywhere by Claire L. Evans

What’s interesting about this to me is that this allows for discovery via other people’s curation rather than algorithms. As Jenny Odell points out in How To Do Nothing, the algorithms of mainstream tech platforms are always streamlining our taste, reducing our personalities down to smaller and smaller sub-categories of taste and feeding this back to us. This closes down pathways instead of opening them up, removing any opportunity for real serendipity.

But connecting to other people, discovering new things and making unexpected connections makes online spaces so much more interesting and alive! Other people are the best curators. For example: NTS is one of my favourite places on the internet because it’s content-driven and entirely powered by people with very good taste. Each show is curated by hand by people who deeply love music. There’s a strong community that anyone can join, either actively in the chatroom or by supporting them financially. They’re always looking for new ways to curate their content: picking their favourites, making themed collections or creating new infinte mixtapes.

On an even more intimate level, this is why I love reading together with friends. I get so much more out of every text by hearing about it from other people’s perspectives. Each person brings their own experiences and interpretations to the same text, making it richer and more multilayered as a result. Through discussing and untangling the text together you create something new in common, taking it to a whole different place.

It is of the nature of idea to be communicated: written, spoken, done. The idea is like grass. It craves light, likes crowds, thrives on crossbreeding, grows better for being stepped on.

▴ Ursula Le Guin

Even without the community element, Obsidian’s backlinks and outgoing links are interesting because they create a network from your thoughts. Individual ideas become less important that the links between multiple ideas.

One of the suggestions of Giles Turnbull’s Agile Comms Handbook (which I reference at work all the time) is to gradually build a narrative over time. I love this approach because it removes the need for each post to be a perfect, polished thought. This makes publishing less intimidating and more like thinking out loud. It allows for your ideas to change over time too.

In this way a blog, comprising a series of posts, can become a digital hyperlinked narrative of thought. New posts can link back to past posts. Teams can document what changes, and show how it has changed. They can show how their minds have changed, and what evidence or research brought those changes about.

This fits with Jay Springett’s and Matt Webb’s advice for publishing online too, which in turn vibes with Julia Cameron’s morning pages practice that I mentioned previously.

Persistent work, created with rhythm, results in an accumulation of creativity. The demonstration of effort, the work of the body, becomes practice.

▴ Jay Springett