— Transformative Work as Livelihood

In December I went to the Free University of Bozen-Bolzano to teach a seminar on Transformative Work as Livelihood for the Eco-Social Design masters students. Over three days, we explored potential pathways available to socially and politically engaged designers, how to balance financial stability with meaningful work, and feminist strategies that ensure that transformative practices remain open to many and viable in the long-term.

Rather than focusing on strategies for individual success, we discussed and imagined new models for working together based on solidarity and care. To do this, we gathered a wide range of practices and tools that challenge the dominant narratives of design and work, exploring the multitude of alternative social and economic approaches that already exist in the here and now.

The seminar cycled between individual and collective exercises: brainstorming, reading, self-reflection and building a toolkit. My goal was to make the seminar really practical, full of useful tools that they could easily apply in their lives, and signposting them towards a broad range of further resources and readings that I’ve found useful in my practice. I wanted to be both critical of our current capitalist reality while also pointing to hopeful possibilities and new pathways. I’ve collected the slides and all the resources into this Arena channel.

I learned so much throughout this process. Below is an overview of what we did, my reflections on how it went and the changes I’d like to make if/when I run this seminar again. I’m documenting this (in probably too much depth) for my own benefit, but if it’s useful for others to read then that’s great too!

Finding common ground

The first afternoon was about finding common ground and defining a collective vocabulary. We did a brainstorming session to collectively unpack the words transformative, work and livelihood, then I defined a few key concepts like reproductive labour, capitalist realism, feminist economics and intersectionality. We discussed some of the central elements of capitalist work economies and how they manifest in design work specifically.

The students shared some of the burning questions that they had about their livelihoods:

- Will I work as a designer? Will I get a job related to what I studied? Will I find a job that I like?

- How do I say no to some opportunities?

- Should I return to my home country? Do I have a responsibility to do this? How do I deal with moving around for work?

- How do I explain what I do and what I want to do?

- How do I create opportunities for the kind of work I want? To what extent should I plan out my career or should I just do what I find fun right now? How do I balance planning with being open to opportunity? How do I stay adaptable?

- How do I deal with uncertainty? What can I do about feeling precarious?

- How do I find jobs through word of mouth or networking?

- Is it bad to use work as a coping mechanism?

- How can I design ethical solutions and not just create more problems?

Livelihoods

Later that afternoon, we went deeper into the concept of livelihood based on Ethan Miller’s book Reimagining Livelihoods, which proposes a new way of looking at livelihoods that expands possibilities for collective agency rather than individualism. His definition of livelihood is much broader than the usual one of making a living — instead it is “open-ended, always-revisable, experimental set of tools for enhancing the capacities of collectives to enact forms of life”.

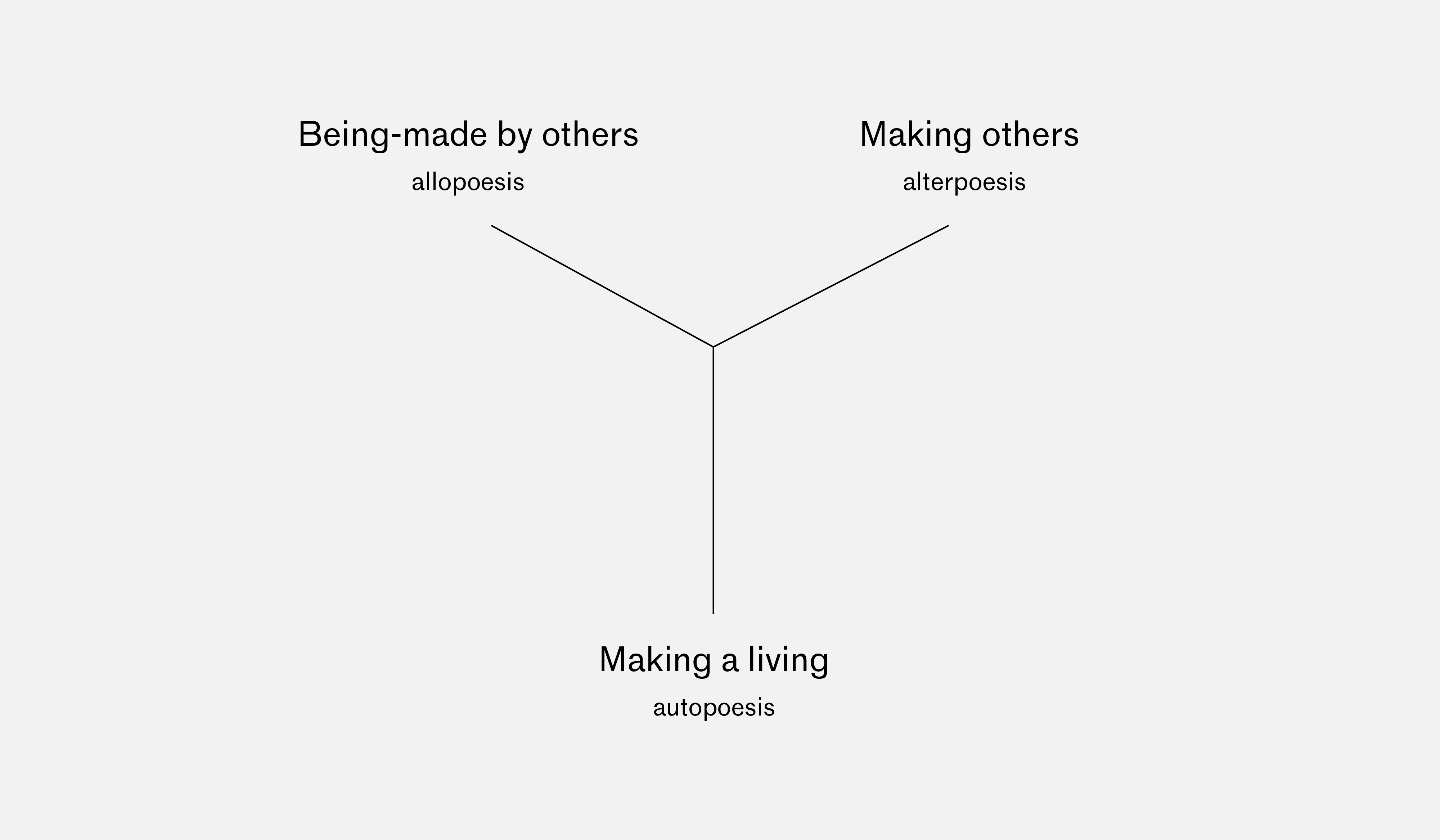

His thinking is encapsulated in this diagram, where livelihood is an ongoing convergence between making one’s living (autopoiesis), having one’s living made by others, both human and nonhuman (allopoiesis), and making livings for others (alterpoiesis). The boundaries between the three are blurred: “making-others can mean being-made and self-making at the same time”. Each student drew their own livelihood triad to reflect upon what they make, receive from and provide for others.

I’m drawn to Miller’s framework because it resonates with my own experiences living and working in collectives. Cooperatives are autonomous self-help initiatives, in which people unite voluntarily to meet their individual and common needs. In cooperatives, autonomy and interdependence are two sides of the same coin — you help others to help yourself. This isn’t about erasing the individual or putting the collective before the individual, but about recognising how working with others can be a means to benefit oneself. Individual freedom is realised through mutual interdependence.

It is difficult to relinquish the illusions of power and delusions of exceptionalism that come with privilege. But it is strangely liberating to realise your true status as a single node in a cooperative network. There is honour to be found in this role, and a certain dignified agency. You won’t be swallowed up by a hive mind or lose your individuality—you will retain your autonomy while simultaneously being profoundly interdependent and connected. In fact, sustainable systems cannot function without the full autonomy and unique expression of each independent part of the interdependent whole.

— Tyson Yunkaporta, Sand Talk

Starting with ourselves and moving outwards

In the same way that interdependence is also about the unique expression of each node, I wanted to explore the idea of care from the scale of the individual to the collective.

Care is less about predetermined behaviours than about a situated, embodied way of responding to interdependence as it shifts across different contexts and temporalities. […] We can disrupt the uncaring attitudes, environments, cultures, economies and structures we inhabit, starting with ourselves and moving outward.

— Alison Place, Feminist Designer

How does self-knowledge and self-development connect to wider challenges? How can we recognise and build upon our own individual experiences without succumbing to individualism?

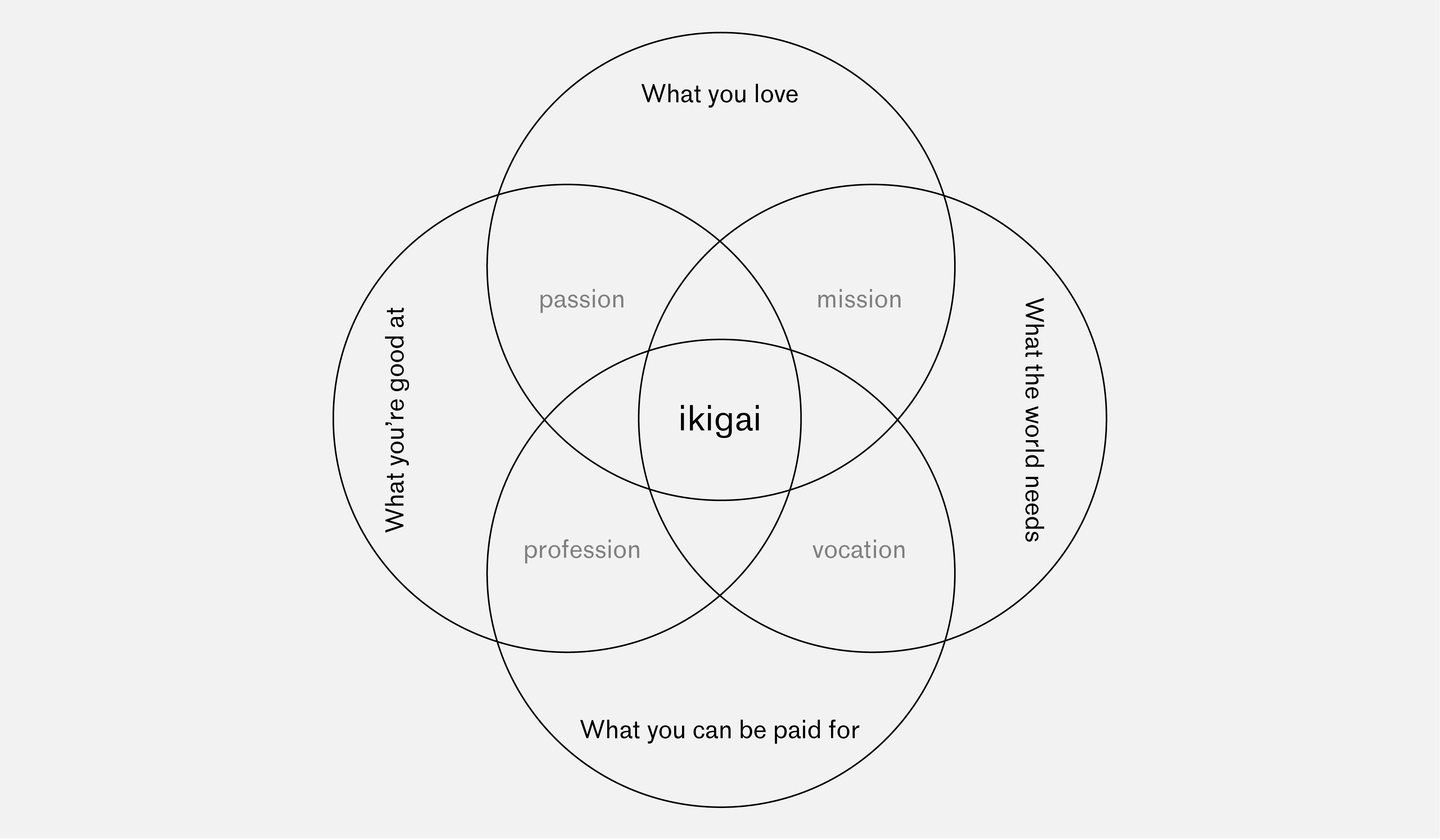

The students each drew Ikigai diagrams to identify what they love to do, what they’re good at, what they can get paid for and what the world needs. The last two questions were the more difficult ones — it’s hard to know what you can get paid to do when you haven’t had much experience yet.

Next time, I would like to come up with a more indirect and creative way to help them answer all these questions more intuitively. It can be hard to directly answer a question like “what do I love to do” in words, but perhaps collaging or drawing would help people look at the question sideways and come up with more unexpected answers that surprise them and deepen their self-understanding.

Around these diagrams, we widened our focus towards mapping relations and resources, adapted from a Diverse Relations Mapping tool developed by Bianca Elzenbaumer as part of the Alpine Community Economies Laboratory.

This exercise prompted them to make an inventory of the social and material resources they had access to, which communities they were already part of and what people they could rely on, in order to identify potential points of leverage and understand where it makes sense to invest more time and energy.

Despite encouraging everyone to use images rather than / as well as words, most students just used words. I think I need to focus on creating an environment that is more conducive to drawing, collaging and mapping: clearing the space, rearranging the furniture so everyone is gathered around one central table, providing more pens and pencils, finding materials to collage with.

I’d also like to come up with some metaphor or visual method to connect or combine these three diagrams (livelihood triad, ikigai diagram and diverse relations mapping). Potentially this could be based on the generative somatics Sites of Shaping, Sites of Change diagram: moving from the self to intimate network, community, institutions and society, with a strong focus on feelings, care and interdependence. Or potentially the permaculture domains.

Principles, models and strategies for transformative work

The second day was about providing them with a broad range of principles, models and strategies for transformative work. We started building our collective toolbox of frameworks, models, strategies and tactics for practising transformative eco-social design.

I began by sharing four sets of principles that guides our work: the cooperative principles, the Design Justice Network principles, Emergent Strategy principles and our own vision, mission and values. Next time, rather than providing an overview of all four, I would choose principle from each and demonstrate how we apply it in our day-to-day work. Otherwise I think ethics and values are just a list of nice sentiments that make us feel good, not really connected to reality or practice.

My favorite way that adaptation with intention and interdependence get practiced is through shared principles. Having clear principles or intentions means, that as conditions change, there is a common understanding of what matters, a way to return to shared practice and behavior.

— adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy

In the assessment, I noticed that many students described their practices as underpinned by “ethics” in general, without defining their ethics in any more depth. I’d like to do some kind of exercise to get them to think about one ethical value, what it means to them specifically and how it connects to their practice. I think I would also reframe it a little to talk more explicitly about politics rather than ethics.

Experimenting with new models

I provided a range of examples of different models for design work (broadly defined), touching on how each organisation was structured, how they work and who they work with. This included other cooperatives like Cooperativa di Disenio, community interest organisations like Migrants in Culture, research organisations like Dark Matter Labs, hyperlocal place-based initiatives like Krater and Floating University and shared workspaces like Extra Practice.

I offered a few different ways of categorising these models. One way was by their relationship to capitalism, as outlined by Graham Jones in The Shock Doctrine of the Left: smashing (direct action), building (infrastructures of support), healing (community responses to oppression) or taming (working within existing institutions to bring about change). We also looked at categorising by type of organisational structure, financial model, context, methods, scale and location.

We did a collective archiving session where each person documented one practice that they were interested in. I would like to make this a more physical exercise in the next iteration, perhaps going to the library to source, photocopy, cut and paste content from interviews with the different practices. Working on computers is no good for collective creativity!

From there, we split into four groups and did a collective brainstorming session to explore these four questions:

- What ethics or values do you think should underlie engaged design practices?

- What forms can eco-social practices or organisations take?

- In which contexts could eco-social designers work?

- What skills do you think engaged designers should have?

On reflection, what was perhaps missing from this spectrum of practices was a focus on career paths that involve working for government or within academia. I am less familiar with these options so the workshop was definitely weighted towards the kinds of practice that I personally know about. In the assessment, most people described wanting to work in or set up their own small practice, but I’m not sure if this is due to a lack of in-depth knowledge about other pathways.

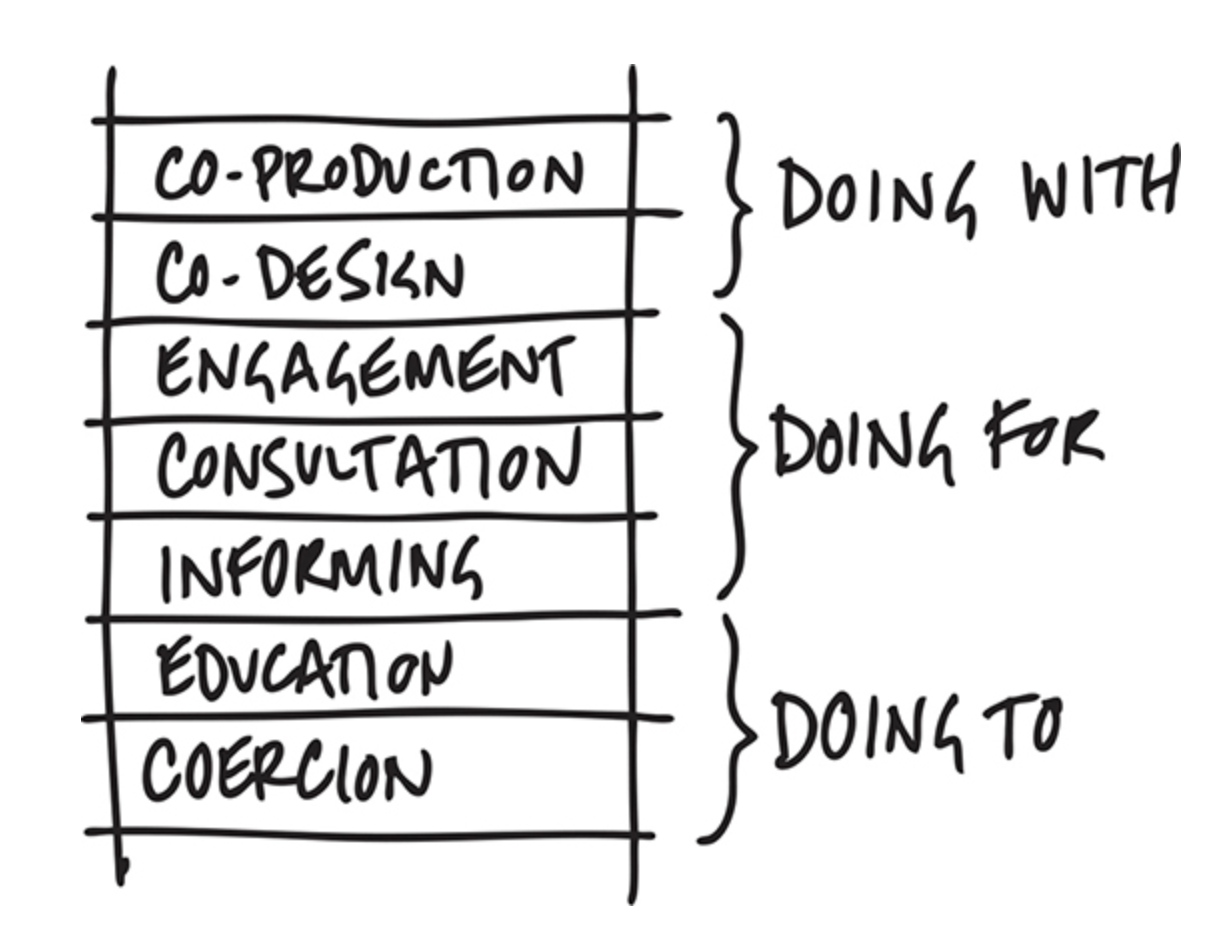

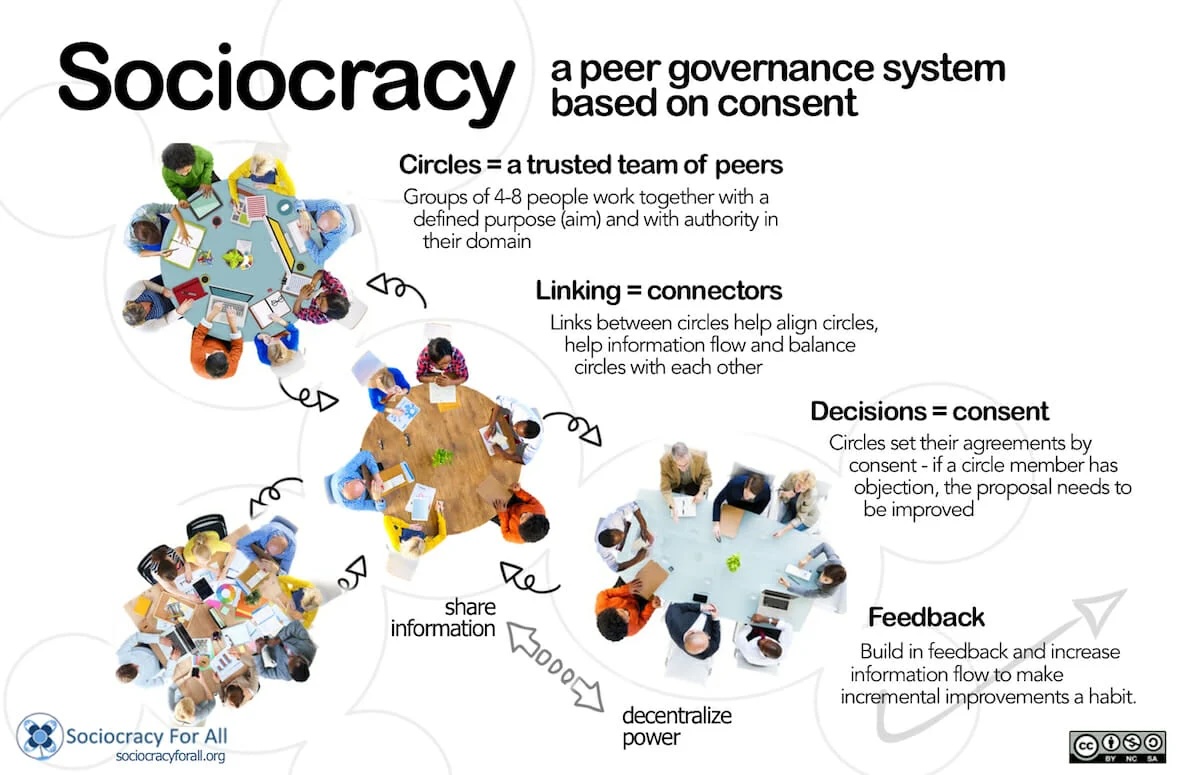

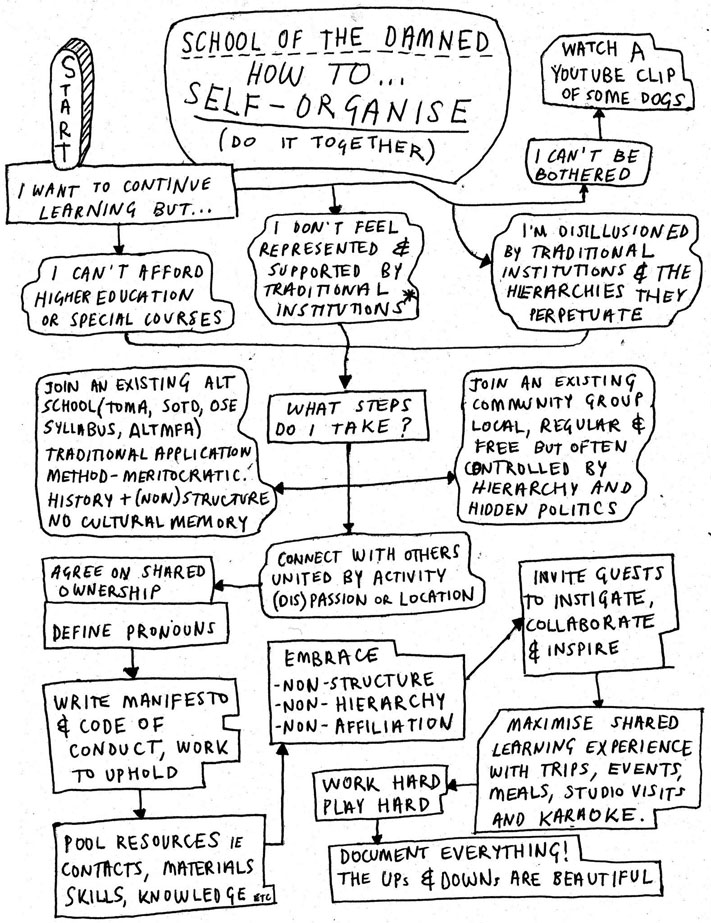

Working with others

In the afternoon, we moved our focus towards working with others. I shared some strategies for democratic, non-hierarchical organising and mutual aid based on my experience working in collectives. We discussed common challenges like making decisions collectively, navigating power and privilege, resolving conflicts, using failure as an opportunity for growth, surviving times of scarcity, and distributing surplus in times of abundance.

We read and discussed Jo Freeman’s 1970 essay The Tyranny of Structurelessness and how this could be applied to collective work today. She suggests tactics like distributing authority and responsibility through transparent and democratic methods amongst as many people as possible, rotating tasks, and ensuring continuous diffusion of information and resources to the group.

I shared the horizontal organising practices that we use within the co-op, and answered their questions about the challenges we’ve faced over the years and how we’ve overcome them.

Next time, I would like for us to practice more of the organising methodologies rather than just just discussing and documenting them. An obvious one would have been to practice making a decision using sociocracy. However, I do think this section would be better suited to a weekly class rather than one afternoon of a seminar, because learning sociocratic techniques is most effective when you’re applying them to an actual collaboration.

This day was too long (9am — 6pm) and everyone was totally exhausted afterwards! I need to intersperse thinking and talking work with opportunities for us to move around, rest, eat and relax. Running this seminar for four hours per day over five days would be even better.

Strategies for collective survival

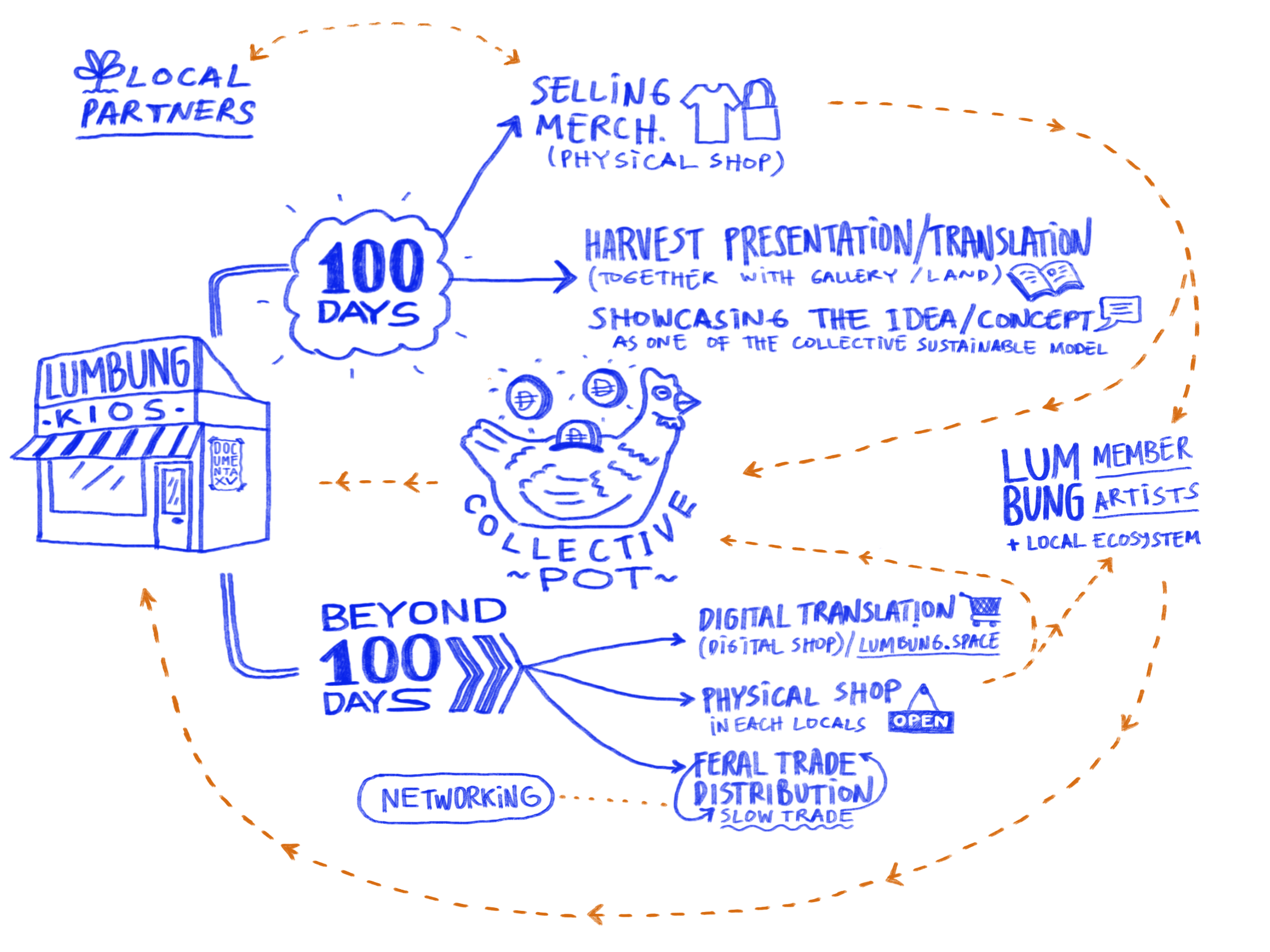

The final day was about developing a toolbox of strategies for collective survival. We discussed the different forms of support we can give each other: material, social, financial and moral. I shared a range of support structures and strategies that I’m aware of, moving from an understanding of the self-as-designer to self-as-worker to self-as-member of an community, industry and society. As with the rest of the seminar, my goal was to start with individual experience but make a direct connection to oppressive systems and how to resist them collectively, rather than just protecting oneself from precarity (if that is even possible).

— lumbung Kios, Harvest by Angga Cipta, 2022

This included a broad range of strategies like:

- Forming collectives

- Starting a shared wallet

- Running events to do tedious freelance admin work together, like Extra Practice do with their ThemeWork sessions

- Joining a renters union

- Living in a housing cooperative

Each student filled out a worksheet with questions from Precarity Pilot’s Creating Fertile Ground for your Practice, which focuses specifically on what students can do during their studies to start on a pathway towards transformative work.

Finally, they worked in groups to come up with ideas for building support structures that they could start while still in university. They were all really engaged with this, I guess because it was more directly linked to their everyday experience and less about speculating on their future.

Again, this day could have been more creative and interactive somehow. It would be good to do less talking (particularly because this was a Friday afternoon after an intense week for all of us) and do more creative and visual work instead — creating a zine or a reader together instead.

Ideal practices

After the seminar, the students had two months to create a short presentation envisioning their ideal practice five years from now, including the kind of work they’d like to do, who they’d like to work with and how, the values that underpin it, the diverse economies that could sustain it and what their day-to-day might look like. I asked them to identify one aspect of their practice that they could easily attain with small adjustments (the next most elegant step) and one aspect that they would need to build towards over the five years.

I think this worked really well and I was super happy with what everyone did. They said that they enjoyed the exercise, particularly the opportunity to be a bit utopian and imagine what their future might be like.

Reflections

Condensing such a huge topic into three days meant that both the students and I were totally exhausted by the end of it. They also seemed quite stressed with all the other work they had to finish before the end of the semester. I provided a bit too much information and I think this overwhelmed them (and me).

If I ran this again, I would aim for less breadth and more depth. Instead of sharing the broadest range of practices and methods, I’d like to choose a few examples and go into depth with them. I need to more clearly connect theory to concrete reality, showing how values and methods manifest in day-to-day work.

I’d like to spend a bit more time supporting them in finding ways to explain what they’re interested in and what they’d like to do. Some “transformative” work pathways are hard to talk about because they don’t exist yet. How can we develop new vocabularies that are also understandable by others?

The challenge with preparing this seminar is that, of course, there isn’t a one size fits all solution to these questions — everyone has their own practices, resources, needs and desires. I based everything on my own experience (working in small studios, participating in collectives, running a worker co-op) but the pathways that many these students will take will be different from this. Last year, Flora Mammana had asked a few friends to record short videos explaining what they did after graduating the masters, which I think is really a good idea.

I would have more moments of doing a variety of gentle, creative, intuitive, meditative and somatic exercises rather than so much thinking work. This might mean making collages, going for a walk together, going to the library, doing breathing exercises or dancing. I would reduce computer work to the bare minimum, and instead do as much as possible with paper and pen. I think a bigger room with less furniture, where we could stick things up on the walls and sit in a circle and move around freely would make a big difference.

Thank you

I’m grateful to Flora Mammana who taught this seminar for the previous two years and recommended that I apply for the position. It was so valuable to be able to hear about her experience and build upon her work while preparing my own version of the seminar. Also for the support and friendship from the UNIBZ professors I met there, including Aart van Bezooijen and Rosario Talevi.

Further reading

Reading list:

- Caps Lock by Ruben Pater

- Capitalist Realism by Mark Fisher

- The End of Capitalism (as we knew it) by J.K. Gibson-Graham

- Doughnut Economics by Kate Raworth

- Reimagining Livelihoods by Ethan Miller

- The Care Manifesto by the Care Collective

- Living a Feminist Life by Sara Ahmed

- Feminist Designer edited by Alison Place

- Design Struggles edited by Claudia Mareis and Nina Paim

- Entreprecariat by Silvio Lorusso

- What Design Can’t Do by Silvio Lorusso

- Who Can Afford to be Critical? by Afonso Matos

- (How) do we (want to) work (together) (as (socially engaged) designers (students and neighbors)) (in neoliberal times)? edited by Jesko Fezer and Studio Experimentelles Design

- The Shock Doctrine of the Left by Graham Jones

- Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown

- Going Horizontal by Samantha Slade

- Self-Organisation / counter-economic strategies edited by Will Bradley, Mika Hannula, Cristina Ricupero and Superflex