It’s so nice to be in north Wales as the seasons change. The beech trees still have the most amazing orange-yellow-red leaves, but now there’s snow at the top of Cadair Idris. It’s wild to think that just three months ago we camped on top of it. There’s a legend that says anyone who sleeps on Cadair Idris’ summit will wake up as either a madman or poet. Three months on and I’m still no better at poetry so…

I’ve been trying to get better at identifying fungi, trees and birds while we’re here. I saw a bright yellow bird the other day which I think is a siskin. There are so many robins around too — I love listening to them sing. I found a database full of recordings of British birds.

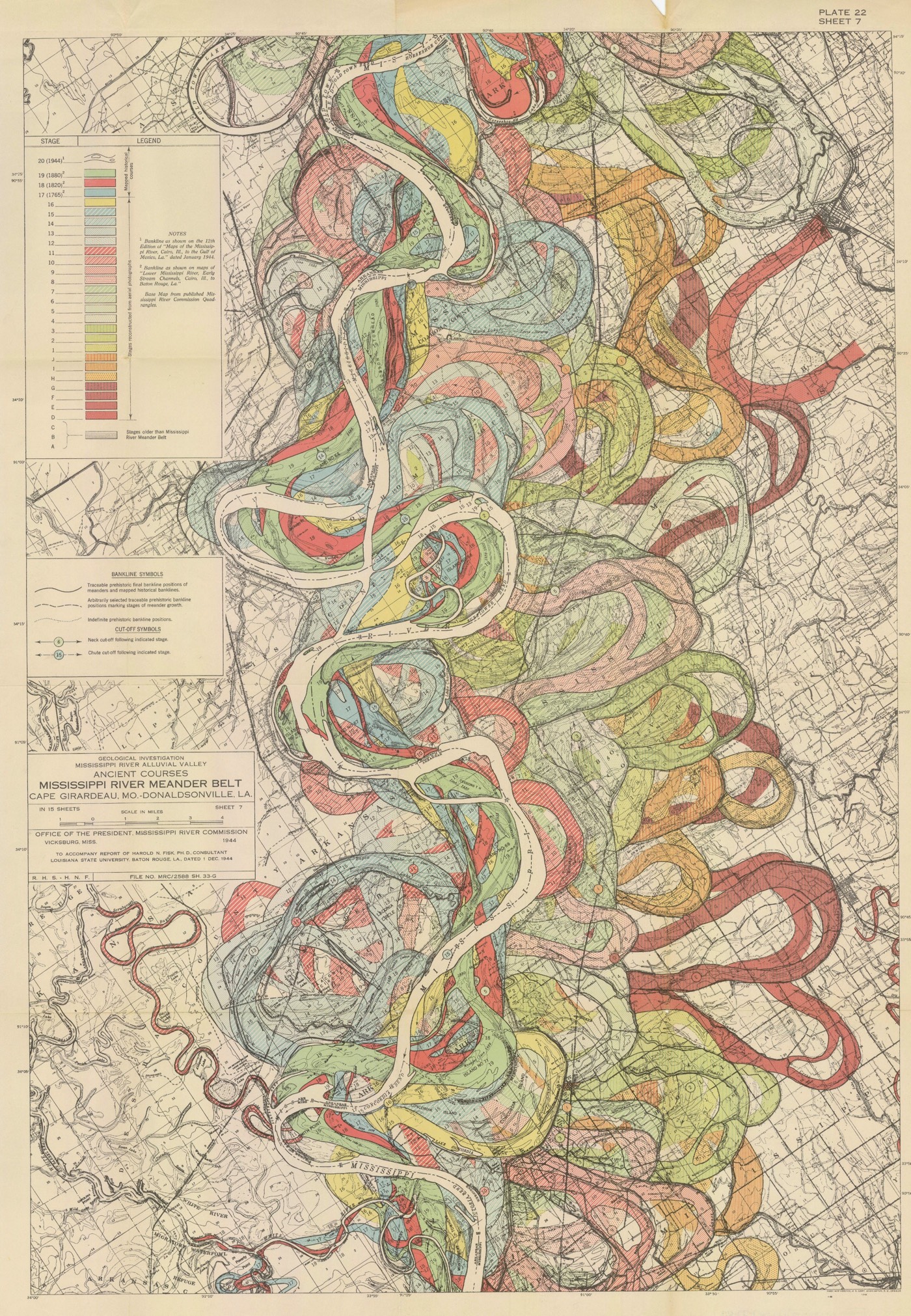

I’m also thinking about water a lot, it’s so incredibly wet here. On the weekends when we go hiking the ground is completely saturated and boggy. The Afon (River) Wnion was the highest I’ve ever seen it a few weeks ago.

Really enjoyed this article What does water want? Most humans seem to have forgotten:

Slow Water mimics or collaborates with natural systems, restoring space for water to slow on land in wetlands, floodplains, mountain meadows, forests, tidal marshes, and mangroves. Slow Water is distributed, not centralised: think of the wet zones scattered throughout a wild watershed instead of a big dam and reservoir. It is also socially just: Slow Water doesn’t take water from some people to give to others, or protect some communities while pushing floods on to another. Slow Water gives communities agency to restore resilience to their local landscapes and revive local cultures. And in taking a systems-oriented approach, it simultaneously supports local water availability, flood control, natural carbon storage, and other-than-human life.

▲A meander map of the Mississipi river by Harold Fisk, 1944

Just west of here the river feeds into the Afon Mawwdach and enters a huge estuary that feeds into the ocean. Fairbourne, a town at the end of the estuary, is the first place in the UK that the government has announced it won’t defend from sea level rise so it’s due to be abandoned by 2054…

c,o,n,t,i,n,u,o,u,s and c-o-n-n-e-c-t-e-d

In Are you the same person you used to be?, they suggest that some people divide their lives up into discrete chapters, constantly reinventing themselves, and others see their lives or identities as one continuous narrative.

I can’t decide which category I belong to. I mostly divide my memories depending on which city I lived in at the time, but I can also see the broader patterns that continue through all my experiences and interests. I guess it’s both.

The article describes research conducted in Dunedin where they studied over a thousand children from the age of three, meeting with them every two years until they were forty-five. They categorised the kids according to their temperaments and watched how they developed over time. How much of our identity is innate and how much is the product of our environment?

Human beings, they suggest, are like storm systems. Each individual storm has its own particular set of traits and dynamics; meanwhile, its future depends on numerous elements of atmosphere and landscape.

▲ An image from open-weather, capturing transmissions from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite

They suggest that although there are some patterns and cycles that are evident from an early age, one way that people can break out of their patterns is through close relationships with others. It reminded me of a bit in The Mushroom at the End of the World, where Anna Tsing talks about indeterminacy:

Fungi are famous for changing shape in relation to their encounters and environments. Many are “potentially immortal”, meaning they die from disease, injury or lack of resources, but not from old age. Even this little fact can alert us to how much our thoughts about knowledge and existence just assume determinate life form and old age. We rarely imagine life without such limits – and when we do we stray into magic. Rayner challenges us to think with mushrooms, otherwise. Some aspects of our lives are more comparable to fungal indeterminacy, he points out. Our daily habits are repetitive, but they are also open-ended, responding to opportunity and encounter. What if our indeterminate life form is not the shape of our bodies but rather the shape of our motions over time? Such indeterminacy expands our concept of human life, showing us how we are transformed by encounter.

Building alternatives

Really good article on Noema by one of the co-founders of my instance Social.coop: Mastodon Isn’t Just A Replacement For Twitter. I was reflecting on the Twitter exodus to Mastodon the other day… It feels to me like a really great example of how important it is to be building these alternatives in parallel to the mainstream.

Acts of smashing, while vital for disruption, do not create the kind of resilient, large-scale, long-term bodies needed to replace dominant powers. As we have seen, the direction our world takes in moments of chaos will be defined by the ideas and institutions that are already available. If we want a world of workplaces owned and run cooperatively, of political decision-making power in local community hands, we stand a much better chance if this is already being built in time for social shocks.

— Graham Jones, The Shock Doctrine of the Left

It is so important to be optimistically building, testing, iterating on these institutions alongside the present day, rather than waiting for some perfect utopia to arrive in which we can start building.

It’s just so easy

Speaking of which, I find it so hilarious that in Victoria 3, a political simulation game, it turns out that communism is the most economically efficient government system:

Capitalist playstyles, they suggest, are too inefficient. The bosses at the top of Victoria 3 capitalist societies get high pay, while workers get very low pay. But in a Victoria 3 communist economy, worker cooperatives ensure that all capitalist wealth is turned over to the workers. As a result, their high purchasing power allows them to spend more money in the economy, which increases economic demand. This leads to higher living standards, which attracts more immigration, another big boost. “It’s just so easy,” the player concludes.

Bits and pieces

- So inspired by Jeff VanderMeer’s experience of rewilding his property in Florida.

- Lots of really useful tips on writing image descriptions here. I also didn’t realise that hashtags should be written in camel case so that screen readers can read each word separately!

- Found a new Substack series on Octavia Butler’s Earthseed.

- It is really relaxing to watch this livestream of waterhole in Namibia. So many critters! (via Matt Webb)

- Great interview with Mindy Seu about her Cyberfeminism Index. I love the idea of YACK / HACK: “YACK is discourse whereas HACK is practice.”

- I’ve been using a hot water bottle to keep warm here because my desk is in the attic below a skylight — extremely cold. Kind of hilarious to see photos of early hot water bottles in this piece from Low Tech Magazine… they look so uncomfortable.

- Love to see some pleasure activism in action: Repair Together are hosting repair raves to help clean up areas of Ukraine.