One of my favourite quotes from Bianca Elzenbaumer of Brave New Alps comes from her 2014 thesis, Designing Economic Cultures:

Aiming to produce critically-engaged content whilst practicing in conventional ways underestimates the substantial potential designers have to contribute to social change not only through the content of their work, but also through their ways of doing and being.

The origin of the word radical is from the root: fundamental, structural. The way that we practice, support ourselves and collaborate with each other hugely impacts the work that we make. If we want to enable radical change, we need to begin by questioning the entire structure of our work.

I think that forming a worker cooperative is one way of prefiguring an alternative vision of the future of work. It recognises that we exist within capitalism, that we need to sustain ourselves within this system, but it also offers an alternative model of working: one based on solidarity, interdependence, self-determination and sustainability, rather than profit, growth and individual success.

Read more

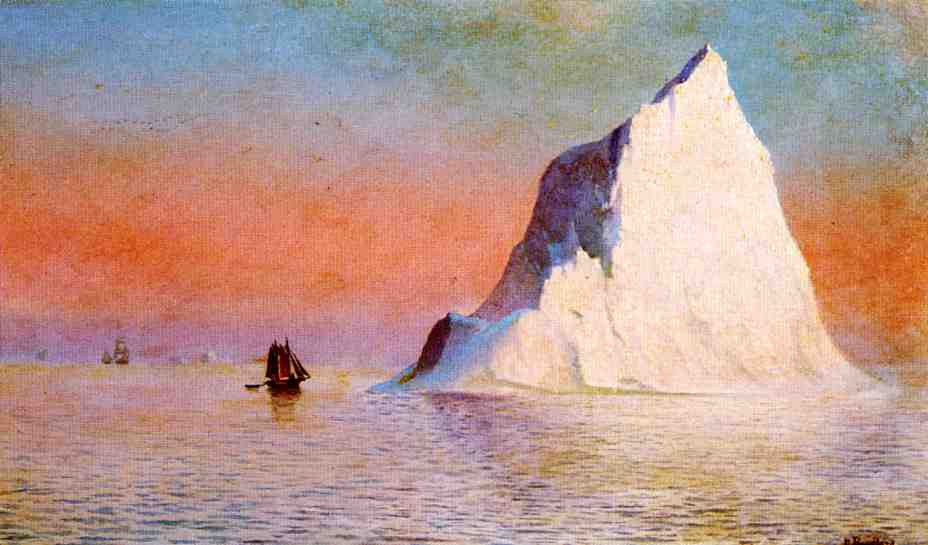

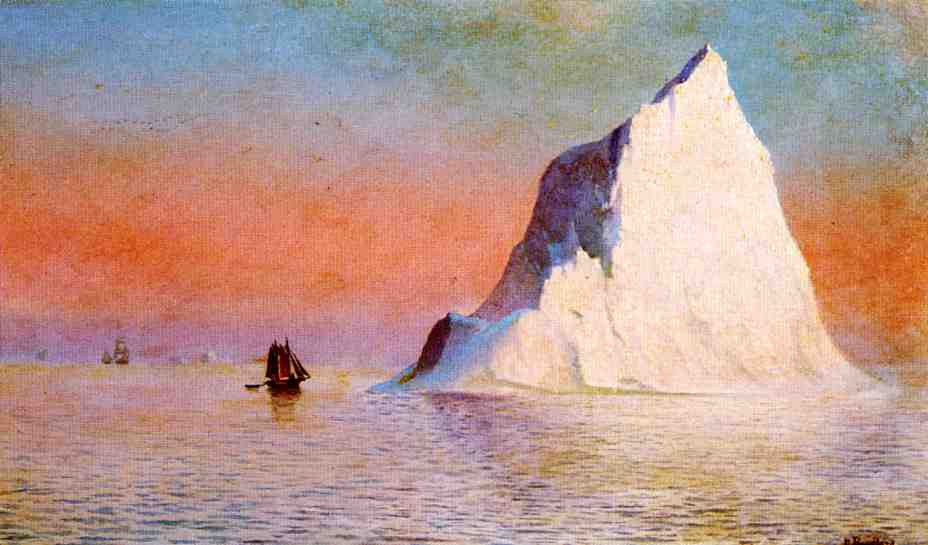

I’m currently in northern Wales, doing a lot of walking and also reading Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet.

It’s a collection of essays about geology and biology, shared histories and unstable futures, nature and the Anthropocene, featuring many of my favourite writers: Anna Tsing, Donna Harraway, Ursula K Le Guin. It’s split in two halves – Ghosts and Monsters:

Ghosts and monsters are two points of departure for characters, agencies and stories that challenge the double conceit of modern Man. Against the fable of Progress, ghosts guide us through haunted lives and landscapes. Against the conceit of the Individual, monsters highlight symbiosis, the enfolding of bodies within bodies in evolution and in every ecological niche. In dialectical fashion, ghosts and monsters unsettle anthropos from its presumed centre stage in the Anthoropocene by highlighting the webs and histories from which all life emerges.

Read more

I came across this toolkit when searching for examples of community-led design practices for a workshop that Sonia and I are currently running (more on that soon).

It explores how artists and communities can work together towards climate justice. It has a few interviews and case studies, accompanied by a few prompts and reflective exercises centred around building collaborative relationships and spaces for dialogue.

I really liked the list of practices at the end, particularly Ambiguity:

Moments of disorientation create space for unpredictable discovery. How can you challenge existing narratives, leave questions unanswered, and introduce new lines of inquiry? Through open-ended practice, how can you create conditions that scaffold communal discovery? How can you begin with questions rather than answers?

It references a few of my favourite writers, adrienne maree brown and Donna Haraway, and has prompted me to finally read Braiding Sweetgrass, which I’ve wanted to do for a while.

I’m collecting more examples of Community-Led Design Practices on Arena.

Alex and I recently spoke to Shane and Kyle from the General Intellect Unit podcast.

We spoke about our work, grassroots organising, and practical details around how to start and run a worker co-op.

(I haven’t actually been able to listen to it yet as listening to my own voice makes me cringe.)

Just read Brave New Alps’ contribution to Design Struggles. The book is available online in full. Their chapter, Design(ers) Beyond Precarity: proposals for everyday action, explores how to create the social and material conditions that make critical, transformative design practice possible.

I’ve done a handful of talks about my work with Common Knowledge and UVW Designers + Cultural Workers, and this is (unsurprisingly) the question that comes up the most from students. It’s one thing to point out all the problems in the industry and outline alternative ways of working, but how does a new graduate with very little experience carve out a critical practice? Where do you even begin?

Read more

This week I’m thinking a lot about Braiding Sweetgrass, because the forest floor is now covered in purple and yellow flowers (ground ivy and yellow anenome, I think).

That September pairing of purple and gold is lived reciprocity; its wisdom is that the beauty of one is illuminated by the radiance of the other. Science and art, matter and spirit, indigenous knowledge and Western science—can they be goldenrod and asters for each other? When I am in their presence, their beauty asks me for reciprocity, to be the complementary color, to make something beautiful in response.

I really liked the book’s focus on reciprocity as a core principle of nature and means of collaborative survival and much else besides.

How do we refill the empty bowl? Is gratitude alone enough? Berries teach us otherwise. […] They remind us that all flourishing is mutual. We need the berries and the berries need us. Their gifts multiply by our care for them, and dwindle from our neglect. We are bound in a covenant of reciprocity, a pact of mutual responsibility to sustain those who sustain us.

A few months ago I spoke at a panel discussion for CSM students. It was a partnership with Thames & Hudson and Design Observer to accompany their new edition of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 1841 essay, Self-reliance. The event aimed to explore what it means to graduate during a crisis after 1+ years of disrupted education.

While I totally agreed with this premise and wanted to contribute, the essay itself and the choice to republish it really grated on me. Of course, it was written in the 19th century, so I can’t really blame Emerson for being a few centuries behind the intersectional feminist, post-colonial and post-humanist thinking. Still, it feels strange to me that the publishers are pointing to the power of individualism as a way to deal with social, political, economical and environmental upheaval. This idea that we’re all individuals and that there’s no such thing as society has been one of neoliberalism’s greatest triumphs.

I wrote a somewhat ranty post about the essay to sort through why I had such a problem with it. I didn’t publish it at the time, but I find myself still thinking about this question of individualism a few months later, so figured I may as well.

Read more