Some of the mushrooms KG and I found in Epping Forest. We managed to find loads of field blewits, which are edible (and delicious)!

Some of the mushrooms KG and I found in Epping Forest. We managed to find loads of field blewits, which are edible (and delicious)!

Minjerribah textures, feat. cute blob, scribbly gum and interspecies crossroads:

I’m currently in northern Wales, doing a lot of walking and also reading Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet.

It’s a collection of essays about geology and biology, shared histories and unstable futures, nature and the Anthropocene, featuring many of my favourite writers: Anna Tsing, Donna Harraway, Ursula K Le Guin. It’s split in two halves – Ghosts and Monsters:

Ghosts and monsters are two points of departure for characters, agencies and stories that challenge the double conceit of modern Man. Against the fable of Progress, ghosts guide us through haunted lives and landscapes. Against the conceit of the Individual, monsters highlight symbiosis, the enfolding of bodies within bodies in evolution and in every ecological niche. In dialectical fashion, ghosts and monsters unsettle anthropos from its presumed centre stage in the Anthoropocene by highlighting the webs and histories from which all life emerges.

A very misty Llyn Cau, halfway up Cadair Idris in Wales.

We hiked most of this trail through low clouds. We noticed it getting warmer as we got closer to the peak, and then suddenly we were above the clouds and in brilliant sunshine.

We made a last minute decision to spend a month on La Gomera, one of the Canary Islands. After six months of rarely travelling outside north London, it feels surreal to be in such a different environment*.

The island is small, roughly circular and very mountainous. This weekend we went for a hike in Garajonay National Park, which was such a contrast to the valley where we’re staying.

The mountains catch the clouds blown in by the trade winds, which means the centre is covered in subtropical forest, called laurisilva. This is the largest remnant of the type of forest that once covered much of Europe and North Africa. It’s quite amazing to wander through… the trees are dripping with lichen and water droplets.

*This is also the closest you can get to the antipodes of Queensland, so I feel right at home.

As of this week, I’m living in Vilnius for a few months while HM does the Rupert residency. Feeling very lucky and inspired.

I’ve been drawing lots of Major Arcana cards, which indicates deep shifts and changes. Feels apt.

I’m simultaneously reading a few books that feel interconnected:

I really enjoyed Kim Stanley Robinson’s writing style in Red Mars, but felt a bit conflicted reading it because I hate the frontier mentality and techno-solutionism that usually comes along with the idea of colonising Mars.

This book is a near future science fiction novel focused back here on Earth. The eponymous ministry was set up to advocate for the world’s future generations of citizens as if their rights are as valid as the present generation’s. Similar to the seventh generation principle of many indigenous cultures.

As Prem Krishnamurthy summarises in his latest newsletter:

It uses the space of fiction to produce a polyphonic, multi-scalar, politically-essential, and thoroughly engaging thought-experiment: a playbook of prototypes for concrete steps to work against climate catastrophe now.

I haven’t finished it yet but I’m thoroughly enjoying it. Particularly how Robinson weaves together scientific and economic ideas for mitigation and adaptation with compelling human stories.

I just finished Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler. I guess you could say I read a lot about climate change and societal collapse. It’s the sequel to Parable of the Sower, which I read about a year ago and loved, but needed a bit of a break before continuing in that world. Butler’s dystopia is so gut-wrenching and horrifyingly prescient.

I saw that adrienne maree brown and Toshi Reagon have a podcast solely focused on the two books, but haven’t listened yet.

An exchange between K Allado-McDowell and GPT-3. Together they muse upon climate change and cybernetics. Some passages are really eerie, and of course the whole time you’re wondering about what consciousness or intelligence (or even authorship) actually means.

When I look at an animal, that’s what I see: intelligence about a biome, compressed and extracted by evolution into a living form. It takes millions of years for life to coalesce in this way, which is why it’s so tragic when species are lost, that the latent space of ecological knowledge is degraded in this way.

We need to save those aspects, those smarts, the way we do when we save books, before they are lost forever. We need to save them in some kind of ‘intelligence library’ somewhere, along with the ocean’s memory of its place in a stable equilibrium with all other life on this planet. And from that place we can construct a new kind of science, one that is closer to the lessons that living things teach us about themselves, and about life on the planet , Gaia, than we have ever gotten before.

I was originally interested in this after reading The DOOM! Report from Nemesis, which is written in the same way and gives a taste of what this book is like. I find Pharmako-AI much more readable and poetic than that essay, though.

I’m also dipping in and out of the Atlas of Anomalous AI, also published by Ignota and edited by Ben Vickers and K Allado-McDowell. I love anything that references the Mnemosyne Atlas.

I was so excited when I saw that the latest Interdependence was with Audrey Tang. This is one of their best episodes so far, imho.

I’ve been so interested in Audrey’s work since reading this article last year. She’s an organiser, coder, politician and poet. Every conversation she has is recorded and published into the public domain. Her approach to politics and what she’s achieved so far is astounding. This episode also really made me want to visit Taiwan.

Some interesting thoughts about how to give non-human entities a say in politics, which reminded me of some of the ideas in Ministry for the Future and also Regen Network.

She mentioned so many interesting things, it was hard to keep up. Including this report from the UN: The Age of Digital Interdependence. I hate reading PDFs on screen but this one looks pretty interesting, if a bit too human-centric.

A book about creating non-hierarchal organisations, which we’re reading as part of the inaugural Common Knowledge book club!

Because I love thinking with mushrooms! They never cease to amaze me. So far, it’s an enjoyable and fascinating book.

A documentary about Miyazaki’s creative process. It’s interesting to see that his talent seems both innate and a lot of hard work. He can capture the energy of an entire story or character in just one sketch, but also has days or weeks where he hates everything that he makes, continuously throws everything out and begins again, or just avoids working all together.

Making collages out of public domain images of lichen, textiles and others bits.

This week I’m thinking a lot about Braiding Sweetgrass, because the forest floor is now covered in purple and yellow flowers (ground ivy and yellow anenome, I think).

That September pairing of purple and gold is lived reciprocity; its wisdom is that the beauty of one is illuminated by the radiance of the other. Science and art, matter and spirit, indigenous knowledge and Western science—can they be goldenrod and asters for each other? When I am in their presence, their beauty asks me for reciprocity, to be the complementary color, to make something beautiful in response.

I really liked the book’s focus on reciprocity as a core principle of nature and means of collaborative survival and much else besides.

How do we refill the empty bowl? Is gratitude alone enough? Berries teach us otherwise. […] They remind us that all flourishing is mutual. We need the berries and the berries need us. Their gifts multiply by our care for them, and dwindle from our neglect. We are bound in a covenant of reciprocity, a pact of mutual responsibility to sustain those who sustain us.

A couple of months ago, we decided that all co-op members should move to a four-day week at no loss of pay. We think it’s a really important demand, an idea whose time has come, and we wanted to try it out for ourselves. So far, it’s been super successful. We all feel happier and like we have a better work-life balance, yet we’re just as—if not more—productive. I’ve written a bit more about why we did this over on the Common Knowledge blog.

For myself, I wanted to have a day off for my own practice, to write and to relax. I also thought that I could use the time to get more involved in the climate justice movement. I immediately went along to a few different remote organising meetings, but they just made me feel even more burnt out. It was too close to my day-to-day work, and I just didn’t have the energy to spend my free time sitting on the dreaded Zoom.

I started looking for an alternative way to spend my day off. I’ve always loved growing plants, and for a while I’ve been trying to learn more about regenerative farming, foraging and food sovereignty. I looked for a community garden near me and found the Golden Hill Community Garden. Luckily, their volunteer day falls on a Wednesday, which I’d already decided would be my day off.

Spending some time helping in the garden has been so restorative for me. I joined in late summer so I got to share in the abundant harvest: each week we harvest some of the veggies and take them home afterwards. They taste so much better than anything you can buy. I (really) love weeding, I love being outside all day, I love learning about all the different plants and how to care for them.

One day Lucy, the community project worker, was talking about how much she likes to flip through the daily log from the previous decade, because she can read about her and the volunteers doing the same activities they do every year: harvesting this plant, maintaining this part of the garden. There’s something reassuring and beautiful about having deep roots in one place, knowing that the same cycle will repeat year after year. It probably seems obvious, but as someone who moves around a lot, I’m really starting to see the appeal in this.

There was actually an article about Golden Hill in The Guardian the other day, about the rise of community gardens. Lucy describes community gardens as “revolutionary in a quiet way”. Lately I’ve been thinking about this a lot — how important it is to find the right type of activism.

I spend everyday at work thinking about grassroots activism (or organising or social change or whatever you want to call it) in some form. Yet for some reason, I always feel guilty, I worry that I’m not doing enough or that I’m a fraud… all that good stuff. I have a lot of eco-anxiety. And I’ve read about how eco-anxiety is problematic and white, so now I have guilt about my my anxiety too. Unsurprisingly, this is exhausting and completely unsustainable. At best, it’s silly, and at worst, it’s counterproductive. You can’t contribute to a movement if you’re burnt out.

Helping out a community garden helps me recalibrate, slow down, spend time away from my computer and see things from a different perspective. In some ways, it feels like an antidote to thinking and reading and talking and worrying about climate change on a daily basis. Rather than thinking about global crises, economic levers, parts per million, I’m thinking on a hyperlocal scale, about the soil and plants right in front of me.

There is such urgency in the multitude of crises we face, it can make it hard to remember that in fact it is urgency thinking (urgent constant unsustainable growth) that got us to this point, and that our potential success lies in doing deep, slow, intentional work.

— adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy

With something as unimaginably huge as climate change, the only viable response is through collective action. However, this can take so many different forms, not just direct action or lobbying. This isn’t to say those things aren’t vital – they are. But everyone can find a role that suits their own particular skills, interests, capacity and strengths. Each role is just as important as the next.

Lots of people have made different attempts at categorising these different roles. In The Shock Doctrine of the Left, Graham Jones describes a four-part framework of mutually reinforcing organising strategies: Smashing, Building, Healing and Taming. Similarly, Bill Moyer identifies four roles in his Movement Action Plan: Helper, Organiser, Rebel, Advocate. I think I’ve always been most interested in contributing by “building” viable alternatives like cooperatives and community groups.

We can do, be, and create whatever we want to see, knowing ours is one effort in the midst of many, and the multitude is where our power lies.

— adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy

The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.

— David Graeber

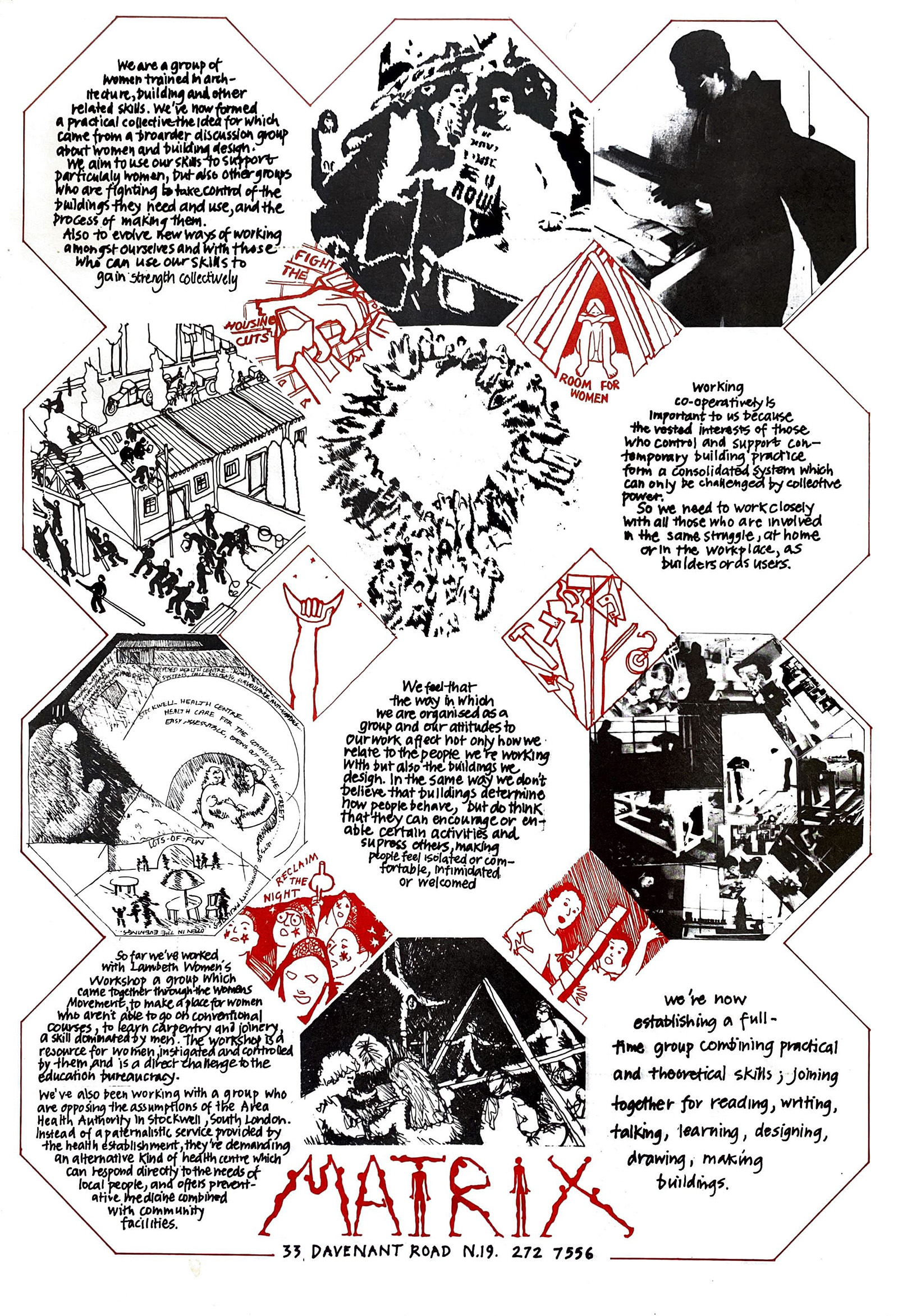

Last weekend we visited How We Live Now at the Barbican, an installation exploring the work of the Matrix Feminist Design Co-operative.

Matrix was a women-led worker co-op that existed in London from 1980–1994. They challenged patriarchal norms and worked in a way that would still be seen as radical today.

They worked in collaboration with people who were usually excluded from the design process, on buildings that were usually ignored by male architects: women’s centres, childcare groups, housing co-ops. They also conducted research, ran a book group and a support group, and educated women in skills like technical drawing, building law and construction practices.

All this while Thatcher was prime minister! So impressive.

— Poster (1979), from the online archive of Matrix’s work

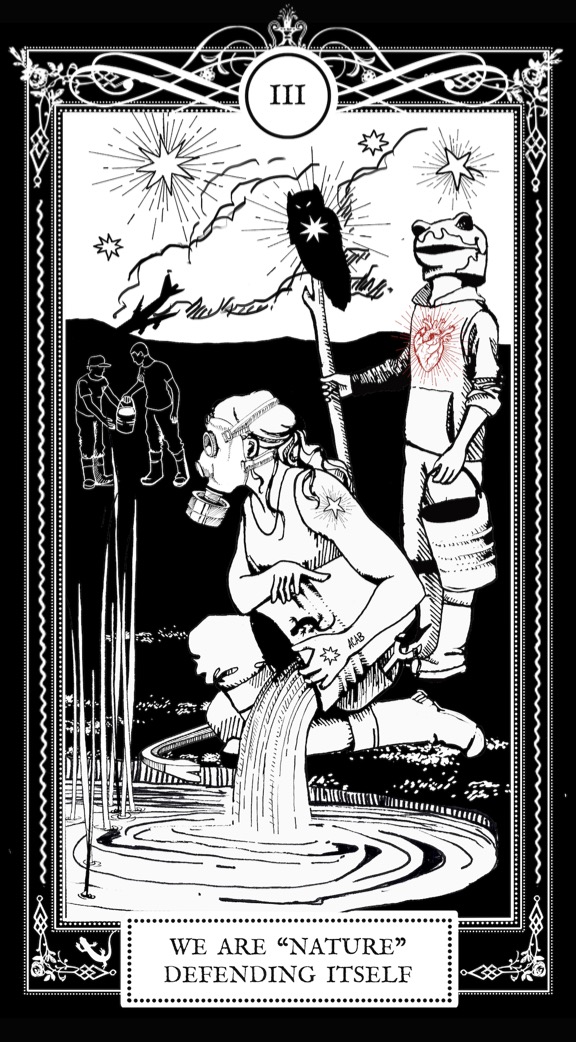

We also went to the launch of a new book called We Are ‘Nature’ Defending Itself: Entangling Art, Activism and Autonomous Zones. The two authors, Isabelle and Jay, coordinate the art activism group The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (among many other things) and live within the ZAD de Notre Dame des Landes.

— Illustration by Amanda Priebe

The ZAD NDDL is an autonomous zone that begun to protest a new airport that the government planned to build on agricultural land. Activists and environmentalists started to squat in the area, alongside local farmers, and gradually built an entire self-organised community.

Over the years there have been several attempts by the state to evict the people living there and destroy their buildings, but this has been met with lots of resistance and solidarity from all over France. The airport plans have now been cancelled: a huge victory, although very hard won. They seem to now have reached an uneasy truce with the state – they’re negotiating for legalisation so they can stay on the land in perpetuity.

Isabelle and Jay told us about their practice and how they ended up at the ZAD. They were working in London (as academics, I think) and doing their art and activism on the side. They don’t see art and activism as two separate things. In their practice, they worked with both, in a participatory and pedagogical way.

At some point, they realised that they couldn’t live in the city any longer. They felt that cities are designed to keep us all divided from each other. They quit their jobs and travelled around Europe for a while, visiting communities and co-living projects throughout.

They settled in northern France for a while and began a housing co-op, but later realised that they still had a mindset of always travelling and moving around for their art practice. They needed to become more grounded into one place, and wanted to find a way to connect art, activism and everyday life. “Why can’t life be art?”

They ended up at the ZAD. They shared stories of the repeated attacks on the ZAD by the state, and the messy, complex, everyday reality of building a commons. You can watch two short documentaries that they made about the history and one about the how people there live now.

They see creation and resistance (yes and no) as two interlocking strands, like DNA. You can’t have one without the other. The counterculture of the 60’s was just about “dropping out” of society and alternative living, which made it easy for Silicon Valley to appropriate its ideals to capitalist ends. This made me think of my post about community gardens. They even said something like “if we don’t resist the extractivist death drive of capitalism, your community garden is going to be underwater.”

Excited to read the book!

Finally, the other day I came across The Reef, a communal living project in Brussels initiated by Edgeryders. I really hope they succeed! I want to live somewhere like this so much.

How and I went back to Australia for about three months during Southern Hemisphere summer. Now we’re back in the UK, enjoying the spring, seeing friends and family and cooperators, discussing lots of books and dreaming about what to do next.

This was by far the longest I’ve spent back there since I left ten years ago. I feel so grateful to have a place like that to go back to, to have the freedom to move, and to see friends and family for the first time in two very strange years.

We mainly stayed in Melbourne and worked remotely, which was a whole new challenge with an 11-hour time difference. We did also go to Queensland to see family, Minjerribah (our usual holiday spot when I was growing up and one of my favourite places in the world), Lennox Head and Brunswick Heads in northern NSW, and Tasmania.

Visiting Tasmania was one of the highlights. It was my first time there and I was so in love with the natural beauty. It’s one of the first places in the world that’s gone carbon negative as they’ve shut down one of their big logging mills, so now their native forests absorb more carbon than the whole state emits. We saw so many animals there that don’t exist anywhere else.

We stayed for a week in a tiny house outside of Hobart. It was so dreamy: a huge window at the front looking out to the bay. They had an outdoor bath where you could look up into the eucalypts filled with birds.

One of our favourite parts of this trip was visiting Paprika and Benjamin in Launceston. They and their house full of books and garden full of veg really inspired us when thinking about how we want to live and where we want to go next.

The worst part of the trip was getting caught in the terrible East Coast floods and having to spend a week in an evacuation centre. More on that in another post, but it was a really intense, visceral reminder of the kind of world that we’re heading towards (that we’re already living in). The depressing thing is that the area flooded again about two weeks after we were there, and now Queensland is flooding yet again.

Now I’m back in London staying with friends while we work out what to do next. It is a joy to be here again, to spend time with people that I’ve barely been able to see for so long.

How and I spent last weekend in a place called Praktyka in Devon and came back very inspired. They spent 18 months travelling the world and visiting other places like retreats and cooperatives to define what kind of space they wanted to build together. I’m really excited to see how it develops.

We’re definitely still in dreaming/planning mode, but How and I are hoping to find somewhere like this that we can make our own, to build a space where we can have friends visit, grow a garden, run a residency and maybe some type of event/community space.

Realistically we’re going to have to move out of south-east England to do this, so it’s been fun to explore the different options of where we could live. We’re hoping to spend some time over summer visiting a few places that are doing similar things in Italy and Spain.

I’m a little nervous of moving out of a city for the first time, particularly one where I have so many connections and there are so many opportunities. But we just feel so excited about the potential of a project like this. When I think about the times that I have been the absolute happiest, it would be summer 2019 when I stayed at Casa Sasso in Gambarogno and with Brave New Alps / La Foresta in Roverto. I just want that but… all the time.

Capital moves people around and draws them to the center: to find your luck you are urged to move from the village to the town, from the town to the regional capital, and from there to the metropolis. […] Resisting capital’s demand for constant movement is for some designers a strategy against precarisation.

Being exposed to precarity implies a constant temporariness, a constant flux of building and abandoning social and material structures, thus missing out on the possibility of creating interlinking infrastructures that can take us and others beyond precarity, infrastructures that can support critical practice through dire times.

– from Design(ers) Beyond Precarity: Proposals for Everyday Action by Brave New Alps

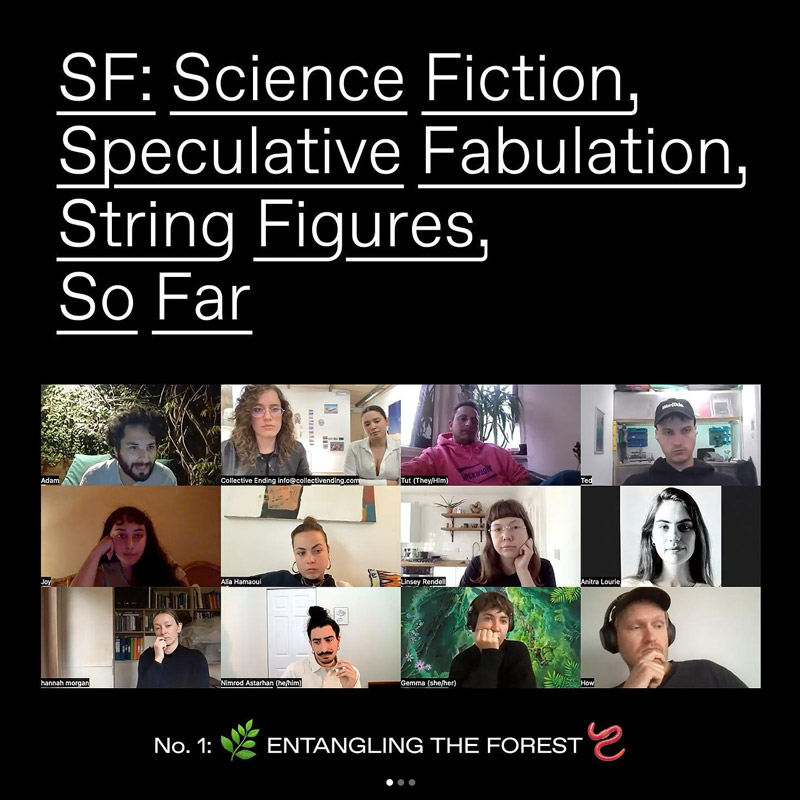

I’ve joined two remote reading groups. Both are open to join if you’re interested, dear reader.

One of them is Rererereading Group, which Paprika and Benjamin invited us to. So far we’ve read Blockchain Chicken Farm, which I enjoyed a lot, and The Question Concerning Technology in China, which I found too complex and philosophical so have dropped out for the time being. I have really enjoyed the calls that I have joined though – it’s just so fun to discuss a text so deeply with a small group and to deepen our understand together.

The other is a feminist sci fi reading group organised by Yuli. In our first session, 🌿 Entangling the Forest 🪱, we discussed Ursula Le Guin’s The Word for World is Forest, Adam Curtis’ All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace and The Daoist Yin Principle in Ecofeminist Novels by Amy Chan Kit-Sze.

I usually hate after hours Zoom calls as it feels too much like work and even during remote lectures I end up zoning out. But I just found this session so engaging and fun. More exciting than a lecture because there wasn’t any hierarchy – just a group of people exploring ideas together. Yuli did a really great job curating the readings so there was so many interlinked topics to dive into which made for a very rich discussion.

Lots of Taoist/Daoist themes running through both reading groups. Next I’d quite like to read Le Guin’s translation of the Tao Te Ching.

I just finished reading a book called The Feeling Buddha, so I’m thinking a lot about mindfulness and spirituality. I also started therapy, and all of these things feel like they’re combining in really generative and healthy ways.

One of the nice things about being in London again is being able to spend time IRL with the rest of the co-op. We’re working from a space called Pelican House now, which is full of other left organisations like The World Transformed, Green New Deal Rising, Autonomy and London Renters Union.

The space got off to a bit of a slow start due to the pandemic, but it’s feeling more convivial now as people settle in. The hope is that the building will become a bit of a hub for the left in London.

At the moment, our co-op is trying to work out how to move into a calmer, slower, more abundant mindset. We’ve always had this as an intention, but the sheer amount of projects we’ve been working on and other pressures outside of our control have meant that we’ve slipped into frantic, scarcity thinking.

I feel really lucky (as ever) to have colleagues that are equally committed to thinking about collective care and addressing burnout. It does feel like things are gradually getting better in terms of our work-life balance.

Quite random, but it seems I’ve temporarily slipped into Beatlesmania after watching the Get Back documentary. I’ve never paid much attention to them before, but the film is a fascinating look into their creative process and their group dynamics. Now I can’t stop reading about them or listening to them. (Hopefully it’s just a phase.)

At the moment I do feel a deep despair at climate inaction and the invasion of Ukraine and the (waves hands) state of the world. But then I’m oscillating between that and an intense gratitude for my present and excitement for our future plans. Trying to just ride the waves and direct these feelings towards doing something meaningful and generative with my time.

Tracing the history of enclosure with Eula Biss, collecting modern stories of commoning with Future Natures, dreaming and planning for a Half Earth Socialist future, and a little bit of solarpunk.

I immediately devour anything written by Eula Biss, so was very excited to see this article by her in the Sentiers newsletter a few weeks ago.

In the essay, she traces the history of the commons and enclosure, which began here in the UK.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common,

But lets the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from the goose.

She debunks that awful essay “The Tragedy of the Commons” by the white nationalist Garrett Hardin. It’s so unfortunately that this idea / phrase has somehow wormed itself into popular consciousness when talking about the commons. It’s been decisively disproven by Elinor Ostrom, who became the first woman to win a Nobel Prize for her work.

One of the things I love about Biss’ work is her ability to weave together so many different strands, wandering across topics like capitalism, feudalism, luddites, gleaners, nostalgia, art, myths, symbols, language, class.

I loved this quote:

The history of the distant past is often speculative. Like science fiction, it gives us a way of thinking about what might be possible, as much as what might have been. In this sense, both the past and the future are imaginary, but real, too, as ideas.

It ties in with the ideas from The Dawn of Everything, which we’re currently reading in Re-re-re-reading Group. In it, the Davids retell history to open up our imaginations, challenge commonly held beliefs and suggest that we might have done life and politics and society very differently in the past (and therefore, we might be able to do it differently again.)

“Would you go back?” strikes me as the wrong question to ask of nostalgia. The question, as Zadie Smith puts it, is how to “restate the things you find valuable in the past… in a way that’s livable in this contemporary moment.” How to locate the commons in a world that is mostly enclosed. How to recover a tradition of rebellion against monied claims to property. How to use machines rather than be used by them. How to be canny, like the workers of the past, and how to be conservationists, like commoners. We can learn from the time before enclosure, but we can’t go back there.

Eula Biss’ other books include Having and Being Had, about money, ownership, capitalism and class and On Immunity, about pandemics, vaccinations, individualism and community. Cannot recommend them enough.

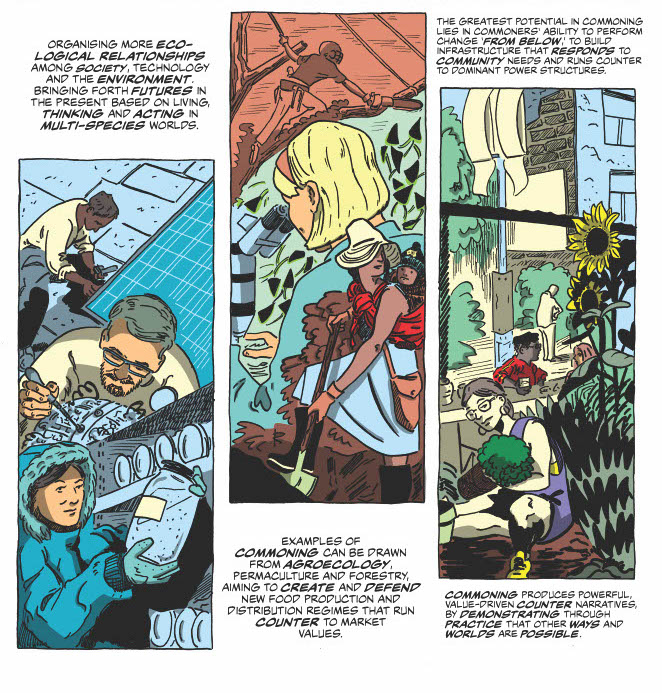

Speaking of the commons, we just launched a new website for Future Natures, which explores the “emergent ecologies of commoning and enclosure through stories, arts and research.” It was such a great project to work on – the team was so easy to collaborate with and their research is so interesting. They have big plans for building up an international network of commoners so I’m really excited to see where it goes.

They’ve created this incredible comic that also explores the history of enclosure, the intersecting crises we’re living through and what commoning is and can be.

I’ve just finished reading Half Earth Socialism by Drew Pendergrass and Troy Vettese.

I was really impressed. It’s a short but dense book that covers a lot of ground, like a non-fiction chaser to The Ministry for the Future. They criticise mainstream environmental solutions, paint a picture of what a socialist utopia might look like (including a speculative fiction chapter inspired by William Morris’ News From Nowhere, which is clunky but quite sweet) and outline a clear plan on how to get there.

Enough should be a human right, a floor below which no one can fall; also a ceiling above which no one can rise. Enough is as good as a feast—or better.

— Kim Stanley Robinson, Ministry for the Future

They also worked with Francis Tseng and Son La Pham to create a Half Earth Socialism game. I played it straight after finishing the book. It was really fun and helped drill home some of their ideas. It felt very moving to be able to pass policies and take action to address climate change, and then to watch as these played out and some of our worst possible futures be avoided.

On the other hand, it felt overwhelming to think on a global scale and 80 years into the future. While I agree with most of the ideas that the book proposes, just the thought of us actually succeeding to implement them at the speed and scale we need feels almost impossible. Still, I think it’s so useful to have these ideas laid out so clearly, as a discussions point or north star.

Your lifetime bridges centuries of harm that set the stage for climate change and centuries of healing that need to start now. Just be a bridge.

– Elizabeth Sawin

We went to the Barbican’s Our Time on Earth exhibition a few weeks ago. It was pretty disappointing. It’s probably partially because I spend a lot of time thinking and reading about these topics already, but the ideas they proposed just seems so cliched/unambitious/self-indulgent. Eirini Malliaraki summarises it well in this thread.

However, I did enjoy the window view designed by Superflux and Sebastian Tiew – love a bit of post-capitalist solarpunk ambiguous utopia!

How and I went for a hike in Snowdonia last weekend. Almost 40km of walking over two days. Over the last few months we’ve gradually been collecting all the basic kit you need for multiday hikes: tent, sleeping mats and bags, backpacks, this incredibly compact wood stove.

It was such an incredible hike. The weather was unusually warm and sunny – I just read that Snowdonia is one of the wettest parts of the UK, so it really was unusual. On the first day, we could see out to the ocean for most of the hike. We swam in a pool fed by a waterfall, walked through ferns and forests and across heather-covered hills. There was a tough bit when Komoot decided to take us across a difficult field without a real path, but we managed to find our way back again.

We camped by a lake (Llyn Du) on Rhinog Fawr. I took these three photos about an hour apart around sunset. Entranced by the changes in light over such a short time.

19:50:25

20:42:50

21:04:09

October is mushroom season! Last Saturday was particularly bright and sunny after a few days of rain, which is perfect for mushrooms. We went to Hampstead Heath with a few friends who forage mushrooms regularly.

We were lucky and found so many different varieties including honey fungus, black-staining polypores, laughing gym, curry-scented milkcap, fruity brittlegill, porcelain fungus, shaggy scalycap and the iconic fly agaric. Most of these were either inedible or poisonous, so we left them alone after identifying them. Some, like the honey fungus, are edible but we didn’t pick them because we found so many other “choice” mushrooms.

The tastiest find of the day was this hen of the woods. We also found some charcoal burners, parasols, cauliflower fungus and red cracked bolete, which we cooked and ate the next day (after extensive rounds of verification and double-checking.)

I enjoy the process of finding mushrooms in itself, even if we didn’t eat them afterwards. It’s all about paying careful attention. It requires a different way of looking: soft, out of the corners of your eyes. There are certain trees, like beech and oak, where they’re more likely to grow around. Once you learn how to see them, it’s like unlocking a hidden visual layer on the world. Suddenly, there are mushrooms everywhere.

To identify the species, you need to pay even closer attention, examining the mushroom’s structure, shape, texture, gills and smell. I’m following Emergence Magazine’s Writing From the Roots course at the moment and identifying mushrooms reminds me of some of the writing exercises we’ve done: gradually zooming in on something and describing it in closer and closer detail each time.

It takes loads of practice to safely forage mushrooms and I’m not sure we would have eaten any without the guidance of our friends. They recommended two apps for identifying mushrooms: Picture Mushroom and Shroomify. I’ve heard that Mushrooming with Confidence is a really useful identification guide that only includes mushrooms that aren’t easy to mix up with a poisonous doppelgänger. There are also good videos online by Wild Food UK.

🍄

The Smart Forests Atlas is a living archive and virtual field site exploring how digital technologies are transforming forests. It provides tools for researchers and other stakeholders to explore, analyse and reflect upon smart forest knowledges and technologies. The Atlas is designed to allow for multiple entrypoints into the research content. Visitors are encouraged to wander through the site according to their own interests, guided by the four wayfinding devices (Map, Radio, Stories and Logbooks).

Alex and I had the pleasure of going to Cambridge to launch the Smart Forests Atlas at The Forest Multiple in October. We’ve been working on the Smart Forests Atlas for a good part of last year, so it was great to publicly launch it.

Read moreIt’s so nice to be in north Wales as the seasons change. The beech trees still have the most amazing orange-yellow-red leaves, but now there’s snow at the top of Cadair Idris. It’s wild to think that just three months ago we camped on top of it. There’s a legend that says anyone who sleeps on Cadair Idris’ summit will wake up as either a madman or poet. Three months on and I’m still no better at poetry so…

I’ve been trying to get better at identifying fungi, trees and birds while we’re here. I saw a bright yellow bird the other day which I think is a siskin. There are so many robins around too — I love listening to them sing. I found a database full of recordings of British birds.

I’m also thinking about water a lot, it’s so incredibly wet here. On the weekends when we go hiking the ground is completely saturated and boggy. The Afon (River) Wnion was the highest I’ve ever seen it a few weeks ago.

Really enjoyed this article What does water want? Most humans seem to have forgotten:

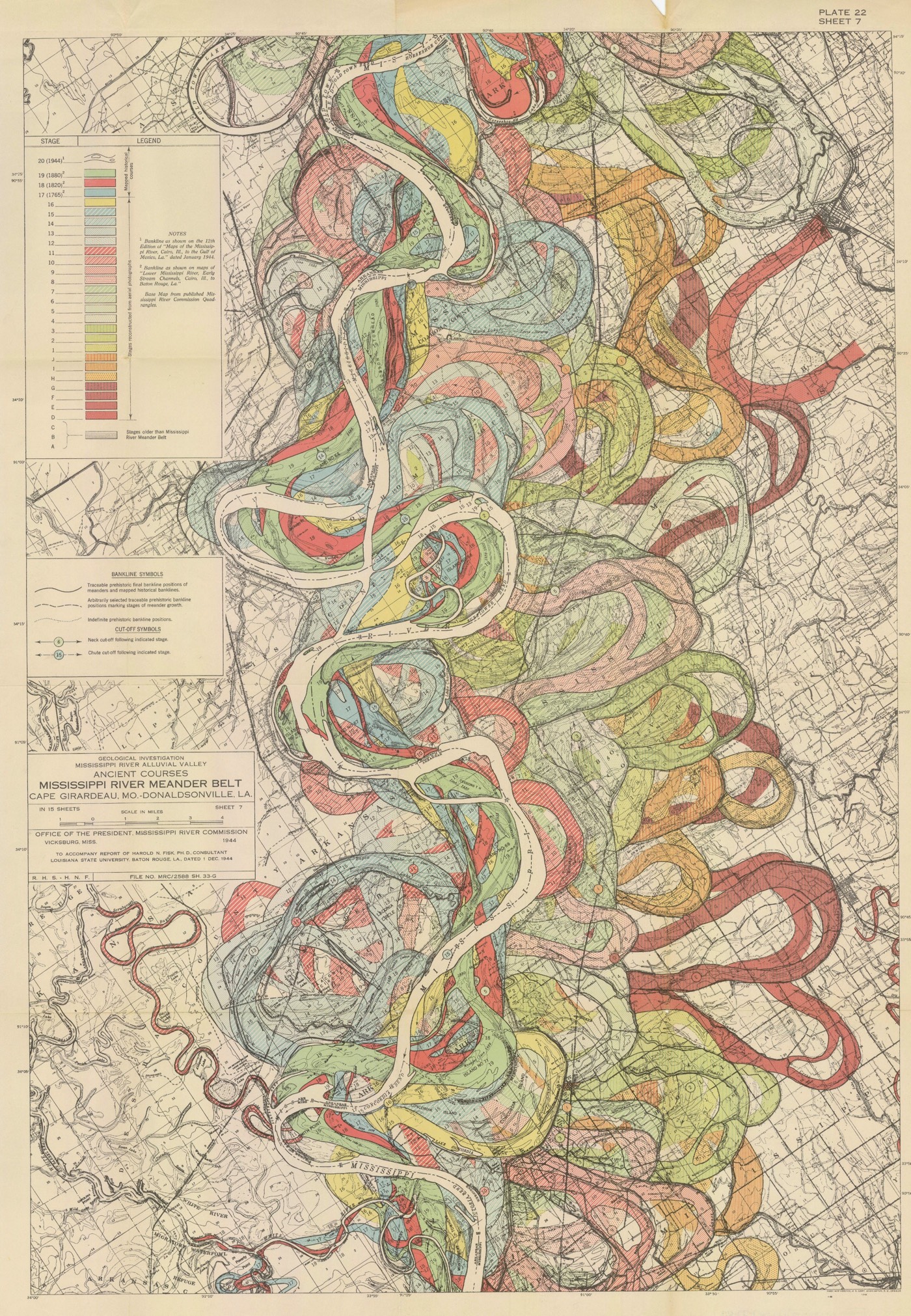

Slow Water mimics or collaborates with natural systems, restoring space for water to slow on land in wetlands, floodplains, mountain meadows, forests, tidal marshes, and mangroves. Slow Water is distributed, not centralised: think of the wet zones scattered throughout a wild watershed instead of a big dam and reservoir. It is also socially just: Slow Water doesn’t take water from some people to give to others, or protect some communities while pushing floods on to another. Slow Water gives communities agency to restore resilience to their local landscapes and revive local cultures. And in taking a systems-oriented approach, it simultaneously supports local water availability, flood control, natural carbon storage, and other-than-human life.

▲A meander map of the Mississipi river by Harold Fisk, 1944

Just west of here the river feeds into the Afon Mawwdach and enters a huge estuary that feeds into the ocean. Fairbourne, a town at the end of the estuary, is the first place in the UK that the government has announced it won’t defend from sea level rise so it’s due to be abandoned by 2054…

In Are you the same person you used to be?, they suggest that some people divide their lives up into discrete chapters, constantly reinventing themselves, and others see their lives or identities as one continuous narrative.

I can’t decide which category I belong to. I mostly divide my memories depending on which city I lived in at the time, but I can also see the broader patterns that continue through all my experiences and interests. I guess it’s both.

The article describes research conducted in Dunedin where they studied over a thousand children from the age of three, meeting with them every two years until they were forty-five. They categorised the kids according to their temperaments and watched how they developed over time. How much of our identity is innate and how much is the product of our environment?

Human beings, they suggest, are like storm systems. Each individual storm has its own particular set of traits and dynamics; meanwhile, its future depends on numerous elements of atmosphere and landscape.

▲ An image from open-weather, capturing transmissions from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) satellite

They suggest that although there are some patterns and cycles that are evident from an early age, one way that people can break out of their patterns is through close relationships with others. It reminded me of a bit in The Mushroom at the End of the World, where Anna Tsing talks about indeterminacy:

Fungi are famous for changing shape in relation to their encounters and environments. Many are “potentially immortal”, meaning they die from disease, injury or lack of resources, but not from old age. Even this little fact can alert us to how much our thoughts about knowledge and existence just assume determinate life form and old age. We rarely imagine life without such limits – and when we do we stray into magic. Rayner challenges us to think with mushrooms, otherwise. Some aspects of our lives are more comparable to fungal indeterminacy, he points out. Our daily habits are repetitive, but they are also open-ended, responding to opportunity and encounter. What if our indeterminate life form is not the shape of our bodies but rather the shape of our motions over time? Such indeterminacy expands our concept of human life, showing us how we are transformed by encounter.

Really good article on Noema by one of the co-founders of my instance Social.coop: Mastodon Isn’t Just A Replacement For Twitter. I was reflecting on the Twitter exodus to Mastodon the other day… It feels to me like a really great example of how important it is to be building these alternatives in parallel to the mainstream.

Acts of smashing, while vital for disruption, do not create the kind of resilient, large-scale, long-term bodies needed to replace dominant powers. As we have seen, the direction our world takes in moments of chaos will be defined by the ideas and institutions that are already available. If we want a world of workplaces owned and run cooperatively, of political decision-making power in local community hands, we stand a much better chance if this is already being built in time for social shocks.

— Graham Jones, The Shock Doctrine of the Left

It is so important to be optimistically building, testing, iterating on these institutions alongside the present day, rather than waiting for some perfect utopia to arrive in which we can start building.

Speaking of which, I find it so hilarious that in Victoria 3, a political simulation game, it turns out that communism is the most economically efficient government system:

Capitalist playstyles, they suggest, are too inefficient. The bosses at the top of Victoria 3 capitalist societies get high pay, while workers get very low pay. But in a Victoria 3 communist economy, worker cooperatives ensure that all capitalist wealth is turned over to the workers. As a result, their high purchasing power allows them to spend more money in the economy, which increases economic demand. This leads to higher living standards, which attracts more immigration, another big boost. “It’s just so easy,” the player concludes.

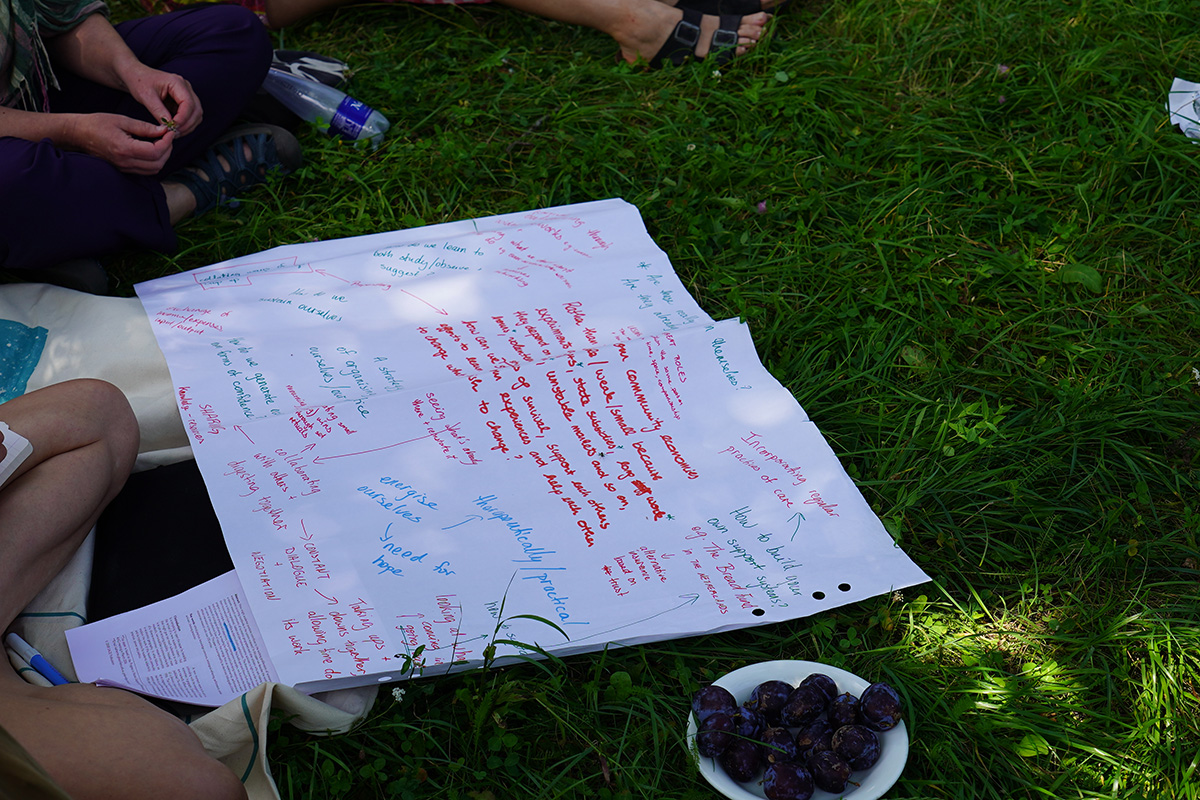

I’ve just come back from an inspiring week at the Community Economies in Action practice retreat in Terragnolo, Italy. It was designed and facilitated by Bianca Elzenbaumer, Kate Rich and Flora Mammana as a practical counterpart to the Community Economies Institute’s summer/winter school.

There were 24 participants with a diverse range of practices: academics and researchers, artists and designers, gardeners and organisers. Everyone was somehow involved in community economies, whether through a food / worker / housing cooperative, ecovillage, market garden, urban landscape, band, radio program, library of things or design lab. Over the week, we learned about all these diverse forms of commoning, exchanged ideas and identified new methods for collaborative survival. We were encouraged to be honest with each other about our struggles as well as celebrating our successes.

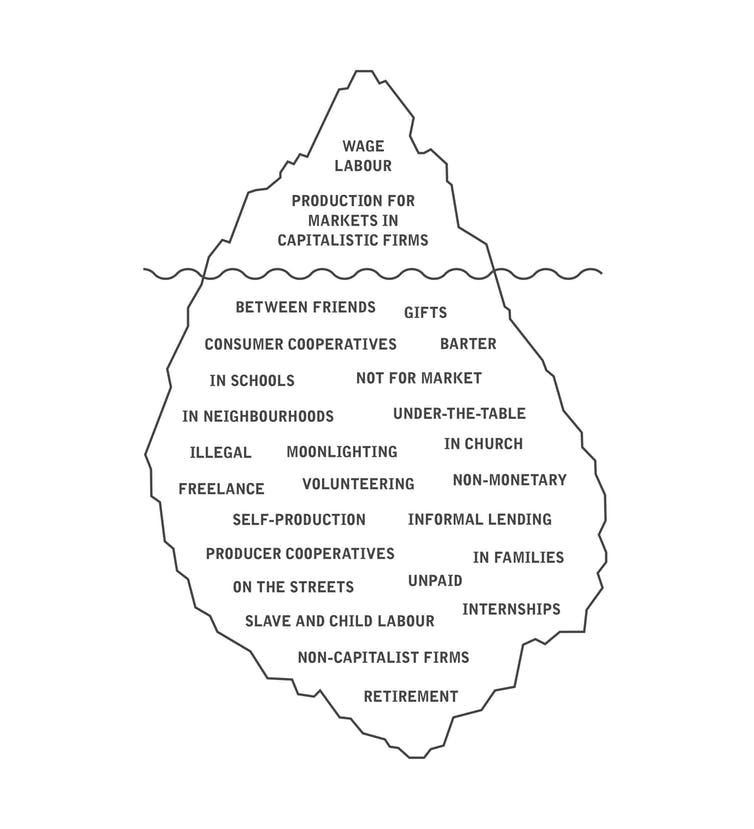

Underpinning the retreat were the ideas of J.K. Gibson-Graham, two feminist geographers from Sydney who collectively wrote books like The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It) and Take Back The Economy. Their work is all about rethinking the economy by foregrounding diverse economic practices and giving them credibility. These diverse economies include unpaid labour, cooperatives, Community Supported Agriculture, alternative currencies, voluntary organisations, underground economies, gift giving, foraging and barter.

▲ Iceberg model diagram by Bianca Elzenbaumer, Brave New Alps

The programme itself was quite emergent, with open spaces where we could propose our own ideas and free time for rest and reflection. Although there were some readings and a lot of deep thinking, there was also a strong focus on connecting with the land and with our bodies. We learned about the long history of commoning in the valley from our host Gianni of Il Masetto. One afternoon we went for a hike on a nearby mountain and foraged edible plants. We did a contact improvisation dance, swam in the river many times and cooked food together.

▲ Photos by Flora Mammana

We read two of their essays and reflected on the conversations they opened with our practices. The first, Economy as Ecological Livelihood by J.K. Gibson-Graham and Ethan Miller, suggested that we need to see the economy as something deeply entangled with everything else (social and ecological) rather than some separate sphere of human activity.

If we cease to think of ourselves as singular, self-contained beings and begin to think alongside, for example, the multiple communities of bacteria and bacterial symbionts from which we continually take shape and of which we are but fleeting, temporary manifestations (Hird 2009; Hird 2010); or if we place our activities in the context of the billions-of-years-old, emergent, planetary-scale process of bio- logical self-construction known as “Gaia” (Lovelock 2000; Harding 2006; Volk 2003), it is no longer possible to identify a singular “humanity” as a distinctive ontological category set apart from all else.

What difference might it make if we accept that from the scale of Gaia, to the scale of the microscopic bacteria that form the laboring basis for nearly all biological energy production and transformation, there is a “we” bound together in myriad interrelationships that are themselves the very conditions of existence for our sense of a human “we”? Being-in-common—that is, community—can no longer be thought of or felt as a community of humans alone; it must become multispecies community that includes all of those with whom our livelihoods are interdependent and interrelated.

They suggest four ethical coordinates to navigate the question “How do we live together with human and non-human others?”:

PARTICIPATION: Who is the “we” that participates in the constitution of livelihoods and community economies? This involves cultivating forms of knowing and becoming that open us to the complexities of our interdependencies, to their animate interactions with us, and to the forms of responsibility this calls forth.

NECESSITY OR SUFFICIENCY: What do “we” need for survival? What constitutes “enough”? This includes asking about what is necessary for the dignified survival of all living beings and communities with whom we are inter-dependent, and about how we might consume in ways such that one species’ or community’s consumption does not compromise the survival chances of others.

SURPLUS: How do “we” produce, appropriate, distribute and mobilize surplus? Our new accounting must include surplus that is generated not just by human labor, but by the work of plants, animals, bacteria, fungi and dynamic energetic systems.

COMMONS: How do “we” make and share a commons, the material commonwealth of our community economies, with this new, more-than-human “we” in mind? Can we, for example, begin to see the chickens, bees and fruit trees of a cooperative farm not as part of that farm’s commons (as shared resources), but rather as living beings partici- pating in the co-constitution of the community that, together, makes and shares the farm?

The second text, Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for Other Worlds, highlights all the diverse economic practices that already happening in the here and now.

Gibson-Graham take a post-structuralist approach to the idea of capitalism. Rather than just adding new or forgotten categories to the existing definition, they instead want to completely restructure how we understand the economy. Economic activities are usually defined in terms of their relationship to capitalism, the master signifier — everything exists in relation to it, whether that’s as a complement or supplement, against or within.

In The end of capitalism we addressed familiar representations of capitalism as an obdurate structure or system, coextensive with the social space. We argued that the performative effect of these representations was to dampen and discourage non-capitalist initiatives, since power was assumed to be concentrated in capitalism and to be largely absent from other forms of economy. In the vicinity of such representations, those who might be interested in non-capitalist economic projects pulled back from ambitions of widespread success – their dreams seemed unrealizable, at least in our lifetimes. Thus capitalism was strengthened, its dominance performed, as an effect of its representations.

They argue that we need to move instead to seeing capitalist practices as one element within a landscape of diverse economies. By moving beyond this capitalocentric viewpoint, we open up space for imagination and new possibilities. We can begin to imagine new worlds that we want to participate in building.

What if we were to accept that the goal of theory is not to extend knowledge by confirming what we already know, that the world is a place of domination and oppression? What if we asked theory instead to help us see openings, to provide a space of freedom and possibility?

▲ Photos by Flora Mammana

We discussed the text together, asking ourselves:

I found the discussion and the overall framing incredibly generative. Rather than seeing ourselves as fighting against some all-encompassing, all-powerful system, it’s about shifting focus to seeing all the diverse possibilities that already exist and that could exist in the near future. Our discussion was focused in on the tangible and the concrete: what we’re already doing, what resources we already have, useful tools and techniques to continue and deepen this work. There is something so optimistic and playful about this approach.

Our interest in building new worlds involves making credible those diverse practices that satisfy needs, regulate consumption, generate surplus, and maintain and expand the commons, so that community economies in which interdependence between people and environments is ethically negotiated can be recognized now and constructed in the future.

We spoke to Katherine Gibson via Zoom one morning. One question that someone asked her was around critique and resistance — how do you keep proliferating possibilities when the whole system is working against you? She suggested that we don’t need to make things harder for ourselves by imagining big bad capitalism always waiting around the corner to gobble up our attempts. It’s easy to be angry at what’s there, it’s much harder to imagine and create desire for the not-quite-yet. You have to imagine that it is possible to create new worlds, working with fragments and wreckages, balancing fighting with building.

We did two mornings of Feral Clinics, a practice adapted from Kate Rich’s Feral MBA and previous iterations of this retreat. Each collective or practitioner took turns hosting a session, arriving with one crucial question that they’re currently facing in their practice. The rest of the group took turns either asking questions or holding space, helping the host to work through their own problems through active listening and thoughtful questions. Rather than asking questions out of your own curiosity, we were encouraged to ask questions based on what the person needed to hear, to help them draw their own conclusions.

In the first round, we helped the host fine-tune their question to the group. In the second round, we helped them proliferate possibilities. In the final round, we helped them identify the next, most elegant steps — a term that adrienne maree brown uses to refer to small, achievable and exciting steps forward, so easy to make that they feel like dancing.

Focus on critical connections more than critical mass—build the resilience by building the relationships.

— adrienne maree brown

The week opened up a lot of questions for me. I found it challenging at times because I started to doubt my own practice, particularly in relation to digital technology. At Common Knowledge, we focus on understanding patterns shared by a broad range of political organisations and using the affordances of technology to help scale up their activities. It felt a long way from the practices of other people there, which was much more place-based, focused on working with their own local community.

I was lucky to have a two-hour mentoring session with Ethan Miller remotely from his housing co-op in Wabanaki Territory / Maine. I feel so grateful for the facilitators for setting this up because there were so many overlaps between the questions I had for my own practice and the work that he’s been doing for decades. We spoke about the challenges of being part of cooperatives and other non-hierarchical organisation models, how they set up their Community Land Trust, feminist science fiction, building capacity and desire within communities, being rooted in a particular place, commoning infrastructure… lots for me to think about!

I found it really heartening that quite a few of the other people there were also puzzled about where to live and how to balance the desire/need to travel with the need to belong to one community. I find it really difficult, as an immigrant from Australia who has lived for the last 12 years in The Netherlands, the UK and now Portugal, to understand where I belong. I also can’t imagine a life where I stay in one place and never travel — I would lose connection with so many of my friends and family, to familiar landscapes and to my past. At the same time, I feel a real need to slow down and feel rooted in one place.

Some of the questions I want to explore further are:

How can we work on a local community level and respond to all the idiosyncrasies of a specific place, but also still make sure we’re connecting with other initiatives, learning from each other, sharing resources and acting in ways that will have an impact on the planetary challenges we face?

When does it make sense to stay small, and when does it make sense to start organising on the national or international level?

What does place-based, small scale, low tech, convivial technology actually look like?

Is there a way to have community if you also need to travel? Can we develop communities across borders, with protocols and rituals than ensure a fair exchange between rooted and transient types? Can we develop new models of kinship and solidarity that enfold all these different needs and contradictions?

How do we create the desire for self-governance and economic experimentation in more people?

PS — How & I chatted to Vida from Robida Collective about the retreat when we visited Topolò last week — listen here.